1University Institute of Applied Management Sciences (UIAMS), Panjab University, Chandigarh, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

The purpose of this study is to empirically test the relationship and effect between innovative work behavior (IWB) and human resource (HR) practices, looking at how particular HR policies and practices encourage innovation and creativity in businesses. Businesses are placing a greater emphasis on innovation in order to stay competitive, therefore it’s critical to comprehend how HR practices support employee-driven innovation. To test the statistical significance, the data was obtained from information technology (IT) professionals working in the IT sector through reliability-tested scales in northern India via a questionnaire and analyzed using SPSS. Correlation and regression analysis were used to examine the data. The study examined important HR aspects and examined how they affect workers’ capacity to generate, promote and execute innovative ideas. Considering the findings, the results showed that IWB is greatly enhanced by HRP that will support employee empowerment, ongoing learning, and intrinsic motivation. For HR managers looking to foster an innovative atmosphere, this article offers insightful information.

HR practices (HRP), innovative work behavior (IWB), SPSS version 30.0.0

Introduction

Organizations nowadays encounter remarkable opportunities and challenges due to the increased competitiveness spurred by globalization, the rapid advancement of technologies, and shorter life-spans of product cycles and services in the 21st century. Organizations must deal with an abundance of issues, such as a lack of innovation and a lack of creative behavior in the workplace. Organizations suffer significant losses when they are unable to compete with other organizations due to a lack of innovative behavior. Therefore, innovation and originality are crucial components to obtain a competitive edge to adapt and embrace the changes taking place in the corporate environment to survive, maintain, and expand in the current dynamic and competitive climate. The continuous effort to innovate is crucial for organizations today. Innovation enhances the value of the organization and plays a key role in the rapidly changing environment to cope with the essential changes to gain a competitive edge over the rival organization (Janssen, 2000). Given the growing significance of innovation, researchers are increasingly trying to determine when and why people behave in innovative ways within their organizations. Scholars contend that achieving such important employee contributions requires the creation and execution of human resource management (HRM) (Guest, 1987). In order to obtain a competitive edge, HRM is commonly regarded to be the management of people and the workplace, comprising both line management and HR specialists. Although extensive study has been conducted over the past two decades, and strategic HRM researchers have agreed that HRM is linked to organizational outcomes, the understanding of the “HRM-performance” relationship, including innovative behavior, is still subject to debate (Nishii et al., 2008). Literature has indicated the importance of innovative work behavior (IWB) and how HRM practices play an essential role in it. Researchers in different articles studied different HRM practices with IWB. Previous research studies have linked the existence of HRM practices, mainly focusing on enhancing skills, motivation, or different opportunities to encourage extra-role behavior on the employee’s side in any particular context.

In general many studies look into the connection between HRP and IWB and has been seen in broad acceptance in the Hotel industry in Pakistan (Jan et al., 2021), the Manufacturing industry in Pakistan (Yasir & Majid, 2020) and Dutch (Bos-Nehlas & Veenendaal, 2019), ICT companies in Thailand (Koednok & Sungsanit, 2018), universities in Vietnamese and cape town (Opoku et al., 2020; Tran et al., 2020), Indian SMEs (Singh et al., 2021) but this study highlights the gap that HR practices and IWB are not covered in the information technology (IT) sector. In developing nations, not enough is known about the best HR practices for managing IT experts for global competitiveness (Kong et al., 2011). The IT/ITES sector is viewed as one of the fastest-growing sectors in India. To be successful in the market, IT companies need to adequately prepare employees for a global environment (Raman et al., 2013). The Indian IT industry is up against a ton of competition and obstacles in the international market. Employees must innovate and adapt to changes to remain competitive. The report will highlight various HR practices influencing innovative behavior among employees and how to improve it as well. Since there is a great need for research in this field due to the service sector’s explosive growth, particularly in the IT sector, this study has looked at how HR practices affect innovative behavior.

Literature Review

For reviewing the literature, the bibliometric analysis technique was used. The keywords used for identifying the articles on the topic were “HRM Practices” OR “HR Practices” AND “Innovative work behaviour” OR “Innovative work behavior.” A total of 27 articles were identified. The VOS viewer software was used to analyse the core authors with six clusters (Figure 1). It was found that HR practices have a significant impact on IWB in different sectors in India and other countries, but the main gap identified from this literature is that the IT sector is still unexplored in this topic (Table 1).

Research Objectives

Hypotheses Development

Based on the objectives and literature review, the following hypothesis is proposed by the researcher:

H1: There is a significant association between HRP and IWB among IT employees.

H2: There is a significant impact of HRP on IWB among IT employees.

H3: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to demographic variables (i.e., marital status, gender, age, years of experience, educational qualification)

H3a: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to marital status.

Figure 1. Network Visualization of Authors.

Source: Vosviewer.

Table 1. Literature Review.

.jpg/10_1177_09747621251329384-table1(1)__630x1177.jpg)

H3b: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to gender.

H3c: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to age.

H3d: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to years of experience.

H3e: There is a significant difference in the levels of IWB among IT employees with regard to educational qualification.

Research Methodology

The sample was selected from the IT companies working in the northern region of India. Middle-level management from IT organizations are the study’s respondents. Questionnaire surveys were used to collect the data. The questionnaire included questions on HRP and IWB. The eligibility requirements set forth for the sample selection process were used to choose the respondents. A total of 250 respondents from IT organizations in the northern region received questionnaires. After the screening process, all irrelevant or incomplete responses were eliminated and the remaining samples included 180 (72%) respondents. A non-probability snowball strategy was used to generate additional connections with respondents. The questionnaire was created in both modes, that is, a self-administered questionnaire and via E-mail digitally.

The data for this study were gathered through a survey method. The questionnaire is divided into three pieces. There are 35 items on the HR practices scale. Responses are gathered using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). The 10-item IWB Scale is included in the second section. The Likert scale included five points, with 1 denoting “never” and 5 denoting “always.” Demographic variables are included as research control variables in the third section.

SPSS version 30.0.0. software was used to analyse the researcher’s hypothetical model using correlation, regression, independent t-test, and one-way ANOVA.

Finding and Analysis

According to reliability analyses, the Cronbach alpha values of every construct are higher than the generally accepted cut-off point of.70. IWB was measured by the 10-item scale of which the alpha value is 0.939. HRP was measured by the 35-item scale of which Cronbach alpha is 0.801 (Table 2). So, it is clear from these results that our scales are valid for measuring the research variables and moving forward with additional analyses to test the study’s hypotheses.

Table 2. Reliability Analyses.

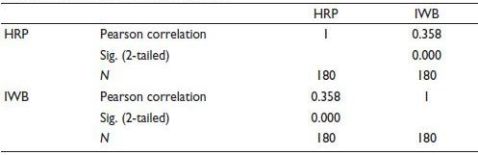

Table 3. Summarizes Correlation Results.

Notes: At the 0.001 level (2-tailed), Correlation is significant.

H1: Correlation analysis.

HRP and IWB have a weak positive and statistically significant Pearson correlation (r = 0.358, p < .001). H1 was therefore supported. This explains that HRP is significantly correlated with IWB. The results are summarized in Table 3.

H2: Regression analysis.

The hypothesis examines the substantial effect of HRP on IWB. To test H2, the dependent variable IWB was regressed on the predictive variable HRP. HRP significantly predicted IWB, F (1,178) = 26.179, p < .001, which shows that HRP can play a key role in shaping IWB (b = 0.465, p < .001). These findings show that HRP has a statistically significant effect on IWB. Additionally, R2 = 0.128 shows that the model predicts 12.8% of the variance in IWB. The results are summarized in Table 4. Hence, H2 is supported. This demonstrates that IWB was affected by HR practices.

H3: Descriptive analysis.

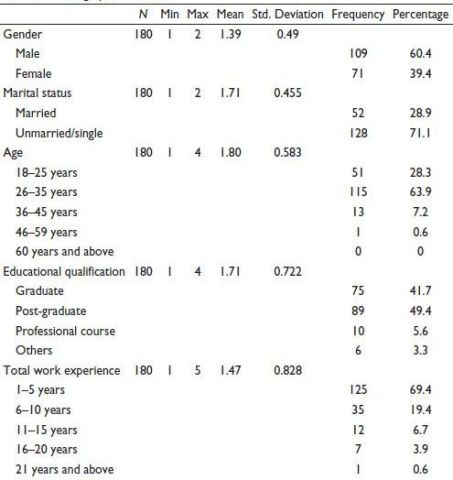

Table 5 reports the demographic details of respondents in the form of gender, age, educational qualification, marital status, and years of experience.

The first demographic variable was gender, in which respondents comprised 109 (representing 60.4%) males and 71 (representing 39.4%) females. After that, marital status in which respondents comprised 52 (representing 28.9%) married and 128 (representing 71.1%) unmarried/single. Next, age in which respondents comprised 51 (representing 28.3%) fall under the age group of 18–25 years, 115 (representing 63.9%) fall under the age group of 26–35 years, 13 (representing 7.2%) fall under the age group of 36–45 years. Next, the educational qualification of the respondents, in which most of them are post-graduate (representing 49.4%). The last demographic variable was years of experience in which the respondents have experience of more than 21 years, comprising 1 (representing 0.6%) respondent, 7 (representing 3.9%) having experience between 16 and 20 years, 12 presenting 6.7%) having experience between 11 and 15 years, 35 (representing 19.4%) having experience between 6 and 10 years and the last 125 (representing 69.4%) having experience between 1 and 5 years.

Table 4. Regression Results.

Notes: p < .001.

Table 5. Demographic Variables.

Table 6. Difference in Job Satisfaction in Married and Single.

H3a: Independent sample T-test.

To compare the IWB of married and single, a t-test of independent samples was used. The scores varied significantly (t (178) = 0.348, p = .728), with the mean score for married people (M = 3.81, SD = 0.76) being higher than that of single people (M = 3.76, SD = 0.71). There was no statistical significance in the magnitude of the mean differences (mean difference = 0.042, 95% IWB: –0.195 to 0.278). The findings are summarized in Table 6. Hence, H3a was NOT supported. The results showed that there was no noticeable change in the degree of IWB among IT professionals based on their marital status.

H3b: Independent sample T-test.

To compare the IWB among males and females, an independent samples t-test was used. The scores varied significantly (t (178) = –0.318, p =.751), with the mean score for males (M = 3.7661, SD = 0.7112) being lower than that of females (M = 3.8014, SD = 0.7539). There was no statistical significance in the magnitude of the mean differences (mean difference = –0.035, 95% IWB: –0.254 to 0.183). The findings are summarized in Table 7. Hence, H3b was NOT supported. This explains that there was no significant change in the levels of IWB among the employees with respect to gender.

H3c: One-way ANOVA.

The hypothesis tests whether IWB differs across varied age groups within the IT professional. IT professionals were put together into five Groups (A: 18–25 years; B: 26–35 years; C: 36–45 years; D: 46–59 years; E: 60 years and above). The findings of the ANOVA indicate that there is no significant distinction between the groups’ scores for IWB. Table 8 shows the summary of the findings. Hence, H3c is NOT Supported (F3, 176 = 0.573, p > .05).

H3d: One-way ANOVA.

The hypothesis tests if IWB differs across levels of experience among IT professionals. So, these employees were put together into five Groups (A: 0–5 years; B: 6–10 years; C: 11–15 years; D: 16–20 years; E: 21 years and above). The findings of the ANOVA indicate that there is no significant distinction between the groups’ scores for IWB. Table 9 shows the summary of the findings. Hence, H3d is NOT Supported (F3, 175 = 1.902, p > .05).

Table 7. Difference in Innovative Work Behavior Between Males and Females.

Table 8. Summarizes One-way Anova Results.

Table 9. Summarizes One-way Anova Results.

H3e: One-way ANOVA.

The hypothesis tests if IWB differs across levels of educational qualification among IT professionals. So, employees were put together into four Groups (Group 1: Graduate; Group 2: Post-Graduate; Group 3: Professional Courses; Group 4: Others). The findings of the ANOVA indicate that there is no significant distinction between the groups’ scores for IWB. Table 10 shows the summary of the findings. Hence, H3e is NOT Supported (F3, 176 = 0.651, p > .05).

Table 10. Summarizes One-way Anova Results.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study sought to explain the connections between employees’ creative behavior and HRM practices (training and development, job security, autonomy, rewards, etc.). All of the constructs’ measuring scales were adapted from the pertinent literature. This study adds to literature knowledge by showing the connection between HRM practices and creative work practices, who work in the IT sector. The proposed model’s variables were examined in connection to one another using SPSS version 30.0.0. The findings showed that IWB and HRM practices are positively correlated. The results were consistent with earlier studies (Bos-Nehlas & Veenendaal, 2019; Yasir & Majid, 2020; Koednok & Sungsanit, 2018; Opoku et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2021; Tran et al., 2020). By observing the direct effects of HR practices on IWB, we have thereby developed a profound grasp of the effects that HR practices have on employees’ creativity. Innovation is essential for long-term success because nowadays organizations operate in a highly competitive and dynamic environment, as creative and original ideas reside in the minds of employees, people are essential to innovation. In the course of their regular work, employees become thoroughly acquainted with the operation and procedures of the company. They are able to highlight any gaps and find possible areas for advancements or enhancements. Employees not only come up with ideas, but also help to secure support for them and eventually see to it whether they are executed successfully because of their conviction, enthusiasm, and dedication. Organizations must understand how to encourage and mold workers’ creative work behaviors.

There are various constraints to this study. The stated hypotheses mentioned in this study were examined based on the perceptions of middle-level employees in the North Indian IT sector, which is the first aspect of the current study. The findings may be more broadly applicable if future research additionally examines how top-level and lower-level employees perceive HR practices and IWB. Therefore, it is important to use caution when attempting to generalize the study’s findings to other domains. Second, cross-sectional data served as the foundation for the analysis. In order to get over this restriction, additional research can evaluate the suggested links using longitudinal data from a different industry or geographic area.

Implications of the Study

As a result of answering the research objectives, the study’s conclusions have significant conceptual and practical ramifications for the worldwide scenario in general and the IT sector of India in particular. The study adds to the HRM literature by validating the links that already exist. The findings will assist managers in making sure that HRM practices are planned to minimize job shifts, employee churn, and feel motivated, which will encourage IT professionals to stay with their existing company even if they are offered opportunities by rivals. Also, if they feel valued at the company, they will remain loyal to their work and that will help to build a long-term relationship with the company. The study affirms that IWB and HR practices are positively correlated. The findings support the widespread implementation of HR practices, which are thought to be crucial for Indian IT companies.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Abstein, A., & Spieth, P. (2014). Exploring HRM meta-features that foster employees’ innovative work behaviour in times of increasing work–life conflict. Creativity and Innovation Management, 23(2), 211–225.

Alfes, K., Truss, C., Soane, E. C., Rees, C., & Gatenby, M. (2013). The relationship between line manager behavior, perceived HRM practices, and individual performance: Examining the mediating role of engagement. Human Resource Management, 52(6), 839–859.

Bos-Nehles, A. C., & Veenendaal, A. A. (2019). Perceptions of HR practices and innovative work behavior: The moderating effect of an innovative climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(18), 2661–2683.

Colakoglu, S., Chung, Y., & Ceylan, C. (2022). Collaboration-based HR systems and innovative work behaviors: The role of information exchange and HR system strength. European Management Journal, 40(4), 518–531.

Datta, S., Budhwar, P., Agarwal, U. A., & Bhargava, S. (2023). Impact of HRM practices on innovative behaviour: Mediating role of talent development climate in Indian firms. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(6), 1071–1096.

Deepa, R., Baral, R., & Saini, G. K. (2024). Proud of my organization: Conceptualizing the relationships between high-performance HR practices, leadership support, organizational pride, identification and innovative work behaviour. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 33(2), 283–300.

Fu, N., Flood, P. C., Bosak, J., Morris, T., & O’Regan, P. (2015). How do high performance work systems influence organizational innovation in professional service firms? Employee Relations, 37(2), 209–231.

Guest, D. E. (1987). Human resource management and industrial relations. Journal of Management Studies, 24(5), 503–521.

Jan, G., Zainal, S. R. M., & Lee, M. C. C. (2021). HRM practices and innovative work behavior within the hotel industry in Pakistan: Harmonious passion as a mediator. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 20(4), 512–541.

Janssen, O. (2000). Job demands, perceptions of effort-reward fairness and innovative work behaviour. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 73(3), 287–302.

Koednok, S., & Sungsanit, M. (2018). The influence of multilevel factors of human resource practices on innovative work behavior. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 13(1), 37–55.

Kong, E., Chadee, D., & Raman, R. (2011, January). The role of human resource practices in developing knowledge and learning capabilities for innovation: A study of IT service providers in India [Paper presentation]. The 10th International Research Conference on Quality, Innovation and Knowledge Management (QIK 2011). University of Southern Queensland.

Mustafa, M. J., Hughes, M., & Ramos, H. M. (2023). Middle-managers’ innovative behavior: The roles of psychological empowerment and personal initiative. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 34(18), 3464–3490.

Nishii, L. H., Lepak, D. P., & Schneider, B. (2008). Employee attributions of the “why” of HR practices: Their effects on employee attitudes and behaviors, and customer satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 61(3), 503–545.

Opoku, F. K., Acquah, I. S. K., & Issau, K. (2020). HRM practice and innovative work behavior: Organisational politics as mediator and personal locus of control as moderator. Journal of Business and Enterprise Development, 9.

Phairat, P., & Potipiroon, W. (2022). High performance work systems and innovative work behavior among telecom employees: The roles of organizational climate for innovation and psychological empowerment. ABAC Journal, 42(3), 214–231.

Raman, R., Chadee, D., Roxas, B., & Michailova, S. (2013). Effects of partnership quality, talent management, and global mindset on performance of offshore IT service providers in India. Journal of International Management, 19(4), 333–346.

Rehman, W. U., Ahmad, M., Allen, M. M., Raziq, M. M., & Riaz, A. (2019). High involvement HR systems and innovative work behaviour: The mediating role of psychological empowerment, and the moderating roles of manager and co-worker support. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(4), 525–535.

Salas-Vallina, A., Pozo, M., & Fernandez-Guerrero, R. (2020). New times for HRM? Well-being oriented management (WOM), harmonious work passion and innovative work behavior. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(3), 561–581.

Singh, N., Bamel, U., & Vohra, V. (2021). The mediating effect of meaningful work between human resource practices and innovative work behavior: A study of emerging market. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 43(2), 459–478.

Thneibat, M. M. (2024). The impact of high commitment work practices on radical innovation: Innovative work behaviour and knowledge sharing as mediators. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 73(7), 2329–2363.

Tran, P. T., Pham, L. M., Do, P. T., & Le, T. A. (2020). HRM practices and employees’ innovative work behavior: An application of the AMO theory. International Journal of Physical and Social Sciences, 10(5), 1–7.

Veenendaal, A., & Bondarouk, T. (2015). Perceptions of HRM and their effect on dimensions of innovative work behaviour: Evidence from a manufacturing firm. Management Revue, 26(2), 138–160.

Yasir, M., & Majid, A. (2020). High-involvement HRM practices and innovative work behavior among production-line workers: Mediating role of employee’s functional flexibility. Employee Relations: The International Journal, 42(4), 883–902.

Zreen, A., Farrukh, M., & Kanwal, N. (2021). Do HR practices facilitate innovative work behaviour? Empirical evidence from higher education institutes. Human Systems Management, 40(5), 701–710.