1Department of Commerce, University of Ladakh, Leh, Ladakh, India

2Department of Commerce, University of Jammu, Jammu and Kashmir, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

In today’s era of fashion, the young population have the tendency to adopt fashionable clothing. Nevertheless, the ever-increasing popularity of sustainability in every walk of contemporary life instils a sense of sustainability when a consumer thinks of fashionable clothes. Therefore, this exploratory study takes a comprehensive approach to unveil the factors affecting people’s behaviour towards sustainable clothes, recognising that human behaviour is dynamic. An offline purposive sampling survey was carried out to collect data from 282 respondents, and data were analysed with the PLS-SEM software. The findings show that determinants like attitude, guilt, willingness to pay, and hedonic value have a crucial role to play in creating sustainable clothing purchase intention among youth in India. Our study is the first to add additional variables to the extended theory of planned behaviour and integrate these variables into a unifying framework for examining their effects on purchase intention for sustainable clothing. Moreover, the study used advanced features like the IPMA of PLS-SEM software to recognise the important factors that aid practitioners in better decision-making.

Environmental consciousness, hedonic value, IPMA, purchase behaviour and sustainability

Introduction

The clothing sector globally contributes substantially to environmental degradation (Apaolaza et al., 2023). Around 10% of the contribution to global carbon emissions is attributed to the ever-increasing consumption of limited natural resources in the manufacturing phase (Cocquyt et al., 2020). The excessive and conspicuous consumption of clothing is characterised by trendy style with affordable pricing and low-quality clothes, resulting in the unnecessary disposal of usable clothing in landfills (Birtwistle & Moore, 2007). This excessive acquisition of clothes and their disposal is sometimes referred to as ‘fast fashion’, and the youth population occupies the major portion (Lundblad & Davies, 2016). Excessive growth in the fashion industry has caused an alarming problem of overconsumption of clothing with little attention accorded to what the cloth is made up of, how long the customer uses it, and where that cloth will end up (Bly et al., 2015). The basis of this trend in consumption is prompt stock turnover, causing an increased number of textiles that ultimately find their final stay in landfills, which could be recycled or reused (Colucci & Vecchi, 2021; Remy et al., 2016). Sustainable clothing has the potential to provide a solution to these issues (Jacobs et al., 2018). Therefore, many clothes manufacturing players are striving hard to push themselves into manufacturing more sustainable clothing that includes eco-friendly production processes, which, among others, comprise using organic dye or reusable materials to manufacture long-lasting clothes (Jacobs et al., 2018; Sadiq et al., 2021). In recent years, marketers and academicians started paying attention to sustainable clothing owing to widespread awareness about environment among consumers, their beliefs, and growing inclination towards eco-friendly commodities (Elf et al., 2022; Saha et al., 2022) because sustainable product features like (reusable materials) have proven to leave a good effect on the intention to purchase fashionable commodities (Grazzini et al., 2021). In emerging economies like India, the annual consumer expenditure is projected to grow much faster, from around $1.5 trillion today to $6 trillion by 2030. In recent years, because of global warming concerns, consumers have shown interest in purchasing green products and living an eco-friendly lifestyle; however, green product purchases have not increased significantly.

This study strives to address gaps in current literature by investigating the role of various factors that shape consumers’ purchasing intentions regarding sustainable clothing, thereby contributing to a clearer understanding of consumer decision-making in this critical area. Analysing these factors in an integrated model will help provide an integrative framework that identifies the factor(s) with a strong influence on the intention to buy sustainable clothes. The study evaluates a model using a group of university students as its sample. The theoretical framework addresses the impact of several variables that shape purchasing intentions and, consequently, encourage the buying of sustainable clothing. Accordingly, this research investigates the key drivers behind sustainable clothing choices. Insights from the findings can assist clothing manufacturers and other stakeholders in recognising factors that support the adoption of sustainable fashion among younger generations. The contents of the article are structured as follows: the next section presents the theoretical foundation of the predictors of sustainable clothing purchasing intention, followed by the methodology, and then a discussion of the results is provided.

Theoretical Background and Literature Review

Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB)

The TPB posits that the inclination of a person to do a specific action influences that individual’s actual conduct. It suggests that whether someone actually does something depends a lot on how likely they are to do it, and that likelihood is governed by three key things: their attitude towards the behaviour, how much control they feel they have over it, and the social pressures they experience. Researchers have been using this theory to look at all sorts of decisions, from why consumers purchase certain products to how they act in environmentally friendly ways (Bamberg & Möser, 2007; Trumbo & O’Keefe, 2005), to the choices they make about clothing and other ethical products (Elliott et al., 2003). When we talk about perceived behavioural control, we are really talking about how easy or hard someone thinks it will be to do something (Ajzen, 1991; Sheppard et al., 1988). This idea is closely linked to self-confidence or self-efficacy (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1969). Attitude is about whether someone expects good or bad results from a behaviour, whereas subjective norms are all about how much people around them think they should (or should not) do it. Researchers believe that our sense of control comes from all the different beliefs we have about what might help or stop us from taking action. Prior studies have explored how this sense of control affects whether people choose environmentally friendly products (Wiederhold & Martinez, 2018). Today, young consumers are aware of the damage being done to the environment, and they are often conscious about what they buy to make a positive difference. According to the TPB, our attitudes are shaped by two main things: what we think will happen if we act a certain way, and whether we see those outcomes as good or bad. Jung et al. (2020) and Kang et al. (2013) advocate that attitude determines a person’s behaviour. Thus, consumers who like sustainable products are more inclined to purchase them (Punyatoya, 2015). Similarly, consumers who hold a favourable attitude towards sustainable clothes will have a higher intention to purchase them.

Subjective norms determine the extent of societal pressure to behave in a specific way. These are the individual perceptions of behaviour that are primarily affected by the judgement of near and dear ones (e.g., family, spouse, friends and societies). These norms are primarily formed on the basis of one’s perception of the expectations of significant others (Manaktola & Jauhari, 2007), and TPB posits that subjective norms are correlated to the intention to adopt pro-environmental behaviour and sustainable clothing.

In the sustainable clothing arena, TPB is being used extensively in research to unveil the critical variables that influence consumers’ intention to buy sustainable clothing. Over the period of time, there have been some well-articulated studies on sustainable clothing (Kim & Oh, 2020; Rausch & Kopplin, 2021). The extant literature reports that most of the studies on sustainable clothing generally studied topics like sustainable fashion, supply chains and sustainable business models, but a limited study has investigated the consumer behaviour perspective on sustainable fashion (Busalim et al., 2022). Furthermore, of those that have studied the issue from the lens of consumer, most of them have primarily emphasised investigating the influence of factors linked to the eco-friendliness awareness of consumers, while a limited studies have addressed the intention to purchase and consumption (Han et al., 2017; Mcneill & Moore, 2015; Park & Lin, 2020). Moreover, prior studies have failed to give conclusive findings on the relationship between consumers’ environmental awareness and their intention to adopt sustainable clothing (Busalim et al., 2022; Diddi et al., 2019; ElHaffar et al., 2020; Rausch & Kopplin, 2021) and reported that buying fashionable clothes is a complex process, as clothing choices are often emotionally tied to personal expression and the desire for social approval, rather than simply serving rational needs (Niinimäki, 2010; Preuit & Yan, 2016). Thus, existing studies highlight the effectiveness of the TPB, revealing that perceived behavioural control, individual attitudes and subjective norms significantly shape intentions to buy sustainable products.

Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H1. Consumers’ purchase intention towards sustainable clothing is significantly influenced by perceived behavioural control.

H2. Attitude significantly influences consumers’ purchase intention towards sustainable clothing.

H3. Subjective norms significantly influence consumers’ intentions to purchase sustainable clothing.

Extended Version of TPB

Over time, researchers and practitioners have introduced additional factors to the original dimensions of the TPB and proposed numerous theoretical models in the research domain of environmentally friendly behaviour to improve the explanatory power of TPB (Gangakhedkar et al., 2023). This is consistent with the recommendation of Ajzen (1991) that more factors can be incorporated into the original framework of TPB, provided such additional variables help in improving the explanatory power of TPB. Therefore, previous researchers have incorporated dimensions such as trust propensity and perceived risk. This study adds environmental knowledge (EK), environmental consciousness (EC), guilt (GU), willingness to pay (WP) and hedonic value (HV) to the original TPB framework.

Environmental Knowledge.

EK has become a scholarly topic lately, not only for researchers but also for people working in the field. When people are aware of environmental issues, they are more likely to pay attention to their choices and think about how those choices affect the world around them (Bamberg & Möser, 2007). In contrast, those who are unaware of the environment are often the ones whose actions do the most harm (Connell & Kozar, 2014). Therefore, understanding environmental problems matters—it helps individuals make more informed decisions on how to use resources and how to avoid damaging the planet (Liu et al., 2020).

In modern days, a substantial portion of clothing is made from petrochemicals, which create a lot of waste and harm the environment. As people learn more about the negative impact of synthetic materials like nylon and polyester, many are turning to eco-friendly fabrics. Now, options like hemp, bamboo and linen are becoming more popular in the fashion industry, replacing traditional materials like cotton and polyester. Studies, such as Liu et al. (2020), have demonstrated that increased EC significantly influences consumers’ propensity to select sustainable products. Thus, it is hypothesised that:

H4. EK positively and significantly affects the consumers’ purchase intention towards sustainable clothing.

Environmental Consciousness (EC).

EC transcends the notion of environmental awareness, incorporating a more expansive and cohesive viewpoint. This study considers it a principal variable within the research framework. EC pertains to the psychological factors that affect a person’s likelihood of engaging in pro-environmental behaviour (Schlegelmilch et al., 1996). This kind of awareness helps people think about things and makes them more responsible (Florka, 2002). EC, as a multifaceted construct, profoundly impacts purchasing intentions (Krause, 1993). Some latest studies report that young Indian shoppers are becoming more aware of environmental damage and are changing the way they shop (Mishal et al., 2017). Hence, our next hypothesis is:

H5. EC has a positive and significant effect on the consumers’ purchase intention towards sustainable clothing.

Guilt (GU).

Guilt is an unpleasant, sad feeling of not ‘being right’ with someone who has been hurt, which makes a person bow their head and avoid looking at them (Izard, 1997). It is the emotion consumers feel while acquiring the product (Goldsmith et al., 2012; Ramanathan & Williams, 2007), including the acquisition of trivial items (Mishra & Mishra, 2011) or engaging in impulsive buying (Miao, 2011). Lindenmeier et al. (2017) conducted a study that revealed a direct and positive correlation between guilt and purchase intention. Consequently, the preceding argument supports the formulation of the hypothesis given below.

H6. Guilt has a positive and significant effect on consumers’ purchasing intention towards sustainable clothing.

Willingness to Pay.

WP is defined as the maximum amount of money a consumer is ready to spend for a product. The financial aspect is the most important determinant for purchase decisions, as rational consumers are price-conscious. A study by Kumar et al. (2021) revealed that Indian youth are ready to spend more on sustainable clothing owing to a sense of EC among them. The existing literature (e.g., Nassivera et al., 2017) reports that although consumers are aware but they show a negative intention to make additional efforts in terms of monetary expenditure, as sustainable clothes are being sold at unreasonably high prices. Whereas Belk (1975) found that the consumer’s monetary situation hinders the consumer from paying more for sustainable clothing. Therefore, we suggest the following hypothesis.

H7. WP has a significant and positive effect on the consumers’ purchasing intention towards sustainable clothing.

Hedonic Value.

HV is a comprehensive term that covers more than mere experience alone and is defined as the value a consumer receives, which is measured in terms of the subjective feeling of fun and pleasure (Babin et al., 1994). Therefore, we have treated HV as one of the determinants in the extended framework. Human beings tend to search for happiness and the avoidance of displeasure. Today’s generation of consumers, being environmentally conscious, shows more interest in buying sustainable clothes. Thus, it is proposed that HV has a positive effect on intention to buy sustainable clothes.

H8. HV positively and significantly affects consumers’ purchase intention towards sustainable clothing.

Purchase Intention (PI) and Purchasing Behaviour (PB).

PI denotes a person’s pronounced inclination or readiness to acquire a specific product in the future (Bagozzi, 1981). Consumers’ inclination to choose eco-friendly products is primarily shaped by their attitudes (Yadav & Pathak, 2016) and their level of EC (Kumar et al., 2017). Intention refers to a person’s readiness to act, while behaviour represents the actual manifestation of that intention (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1969; Bagozzi, 1981; Hassan, 2018; Yadav & Pathak, 2016). Prior research (e.g., Morren & Grinstein, 2016) suggests that the likelihood of intentions translating into actual behaviour is generally higher in developed markets. Nonetheless, the literature remains indeterminate owing to the effect of different socio-cultural contexts. Consumers are more likely to go for eco-friendly products when they develop good feelings about them (Cheah & Phau, 2011). Consequently, individuals who genuinely desire to purchase eco-friendly apparel are more inclined to do so. Recent studies on sustainable consumption have begun to study the mediating role of PI in the link between TPB variables and consumer behaviour. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H9. PI significantly influences the consumers’ PB towards sustainable clothing.

H9a. PI mediates the relationship between perceived behavioural control and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9b. PI has a mediating effect on the relationship between attitude and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9c. PI has a mediating role in the relationship between subjective norms and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9d. PI positively mediates the relationship between EK and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9e. PI plays a mediating role in the relationship between EC and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9f. PI mediates the relationship between guilt and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9g. PI mediates the relationship between WP and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

H9h. PI mediates the relationship between HV and purchase behaviour towards sustainable clothing.

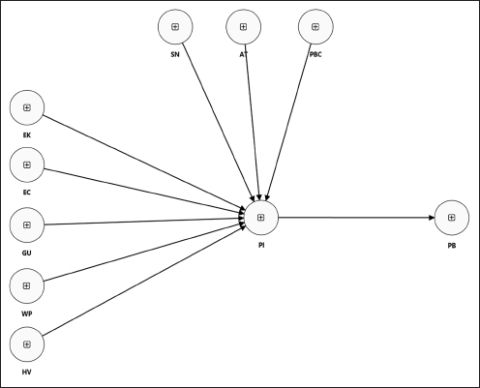

Additionally, previous literature has highlighted the gap in studying the PI and purchase behaviour in the sustainable clothing area, clearly implying that more research on both domains is needed as human behaviour evolves. Hence, the present study emphasises investigating the variables that have an effect on a person’s intention to opt for sustainable clothing. Relevant existing studies reported the impact of attitude, past buying behaviour, financial risk and peer influence in a sustainable clothing context (Aldilax et al., 2020; Shukla, 2019). However, there seems to be a lack of research that studies the role of EK, EC, guilt, WP and HV in the PI of sustainable clothing in the Indian context (Kuswati et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020). Therefore, our study added these variables to the extended TPB and incorporated them into the theoretical framework as presented in Figure 1.

Research Methodology

Sample and Data Collection

The primary data were collected from respondents using a closed-ended questionnaire through the purposive sampling method. Each respondent was contacted in person and assured that their answers to questions would remain confidential. Out of the total 288 respondents who initially agreed to participate, usable responses from 282 respondents were retained after excluding six outliers identified through box-plot analysis (see Table 1). To ensure the validity of the survey instrument, a pilot survey was first done with 54 students, and the questionnaire was finalised after due consultation with two academic experts. Items of the latent variables were adapted from the existing literature, and the respondents were requested to mark their responses on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5, with 5 representing ‘strongly agree’ and 1 ‘strongly disagree’.

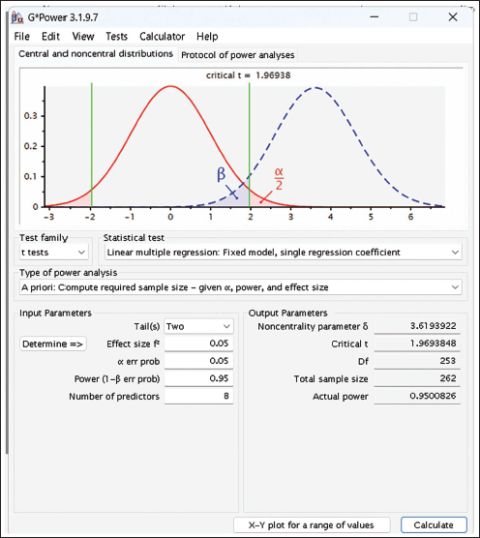

The extant literature suggests a minimum of ten times the maximum number of paths that lead to the endogenous latent variable as a sufficient sample size for PLS-SEM analysis (Hair et al., 2017). However, to ensure robust results, researchers are generally advised to follow more sound and scientific recommendations, for example, software like G*Power (Hair et al., 2018), as it considers statistical power and effect sizes into account. A bare minimum sample size of 262 (Figure 2) was suggested as appropriate for the given parameters by G* Power Software (Faul et al., 2009) and data from 288 respondents, which is more than the bare minimum.

Figure 1. Theoretical Framework.

Data Analysis

Data were analysed using partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). Previous literature recommends using PLS-SEM since it is appropriate for exploratory research and does not require the assumption of normal distribution of data (Hair et al., 2019). As a data analysis technique, PLS-SEM works well on different sample sizes and is not restrictive in its assumptions (Hair et al., 2011). Therefore, Smart PLS 4 software version 4.1.0.1 (latest) was used.

Results

Common Method Bias

The study, being cross-sectional, is susceptible to common method bias (CMB), which arises from the measurement method rather than the structural relationships within the model. An assessment for CMB was conducted before model evaluation to address this potential bias. To identify any signs of CMB within the dataset, a complete examination using the full-collinearity approach was done. This approach involves testing the inner VIF values of all constructs vis-a-vis a random dependent variable, with a value exceeding 3.3 indicating the presence of CMB (Kock & Lynn, 2012). All inner VIFs of constructs were less than 3.3, confirming that the data set is free of CMB (Kock, 2015).

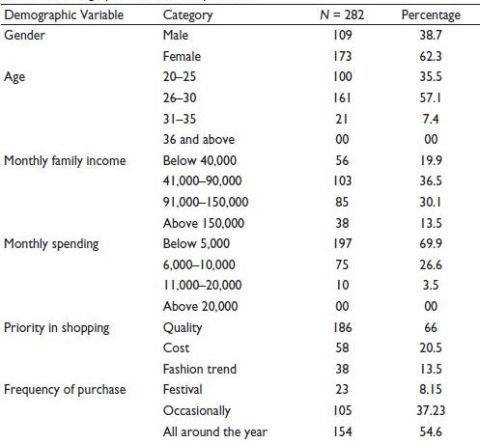

Table 1. Demographic Profile of Respondents.

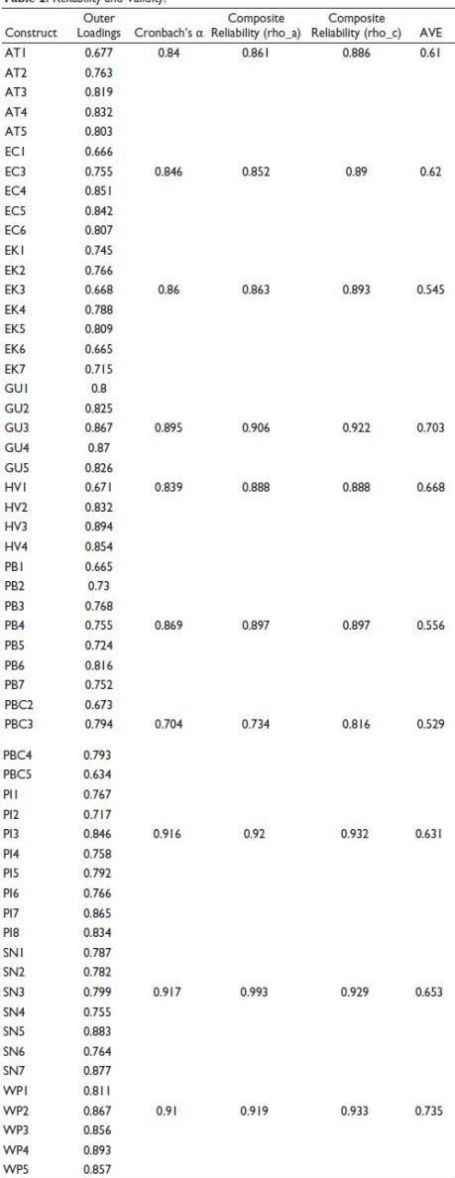

Measurement Model Analysis

The measurement model analysis involves evaluating item-level reliability, internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity (Hair & Alamer 2022). If the outer loadings of an item are higher than 0.708, item-level reliability is confirmed (Hair et al., 2019). Two items related to perceived behavioural controls and one item related to EC had loadings below 0.5 in our study, so we left them out (Hair et al., 2014). We kept items with outer loadings between 0.5 and 0.708, though, because their construct-level AVE was above 0.50 (Hair et al., 2014). Also, as Table 2 shows, five-factor loadings are above 0.6, and the rest are well above 0.708, which means that indicator reliability is confirmed. We used both conservative and liberal measures of Cronbach’s α and composite reliability to check how reliable the constructs were. All latent variables exhibit reliability within the range of 0.70 to 0.95, thereby affirming overall reliability (Dijkstra & Henseler, 2015).

Figure 2. Calculation of Minimum Sample Size.

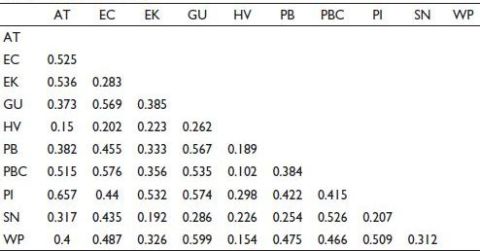

For checking convergent validity, the average variance extracted (AVE) is calculated. This shows how much a latent construct explains item variance and supports its validity. The model’s ten constructs all have an AVE greater than 0.5, which confirms that they are all internally convergent and valid. Discriminant validity measures how different each construct in a model is from the others. The heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio is widely employed in existing literature to check the discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). Our data underwent scrutiny for checking the discriminant validity, with values below 0.85 observed for all constructs in our model, thus affirming discriminant validity (refer to Table 3).

Table 2. Reliability and Validity.

Table 3. HTMT Criterion.

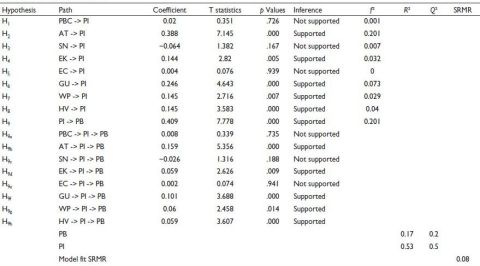

Structural Model Assessment

The first step in assessing the structural model is checking for inner VIF values to detect multicollinearity problems. In the study, VIF values fall below 3, thus ruling out the problem of multicollinearity (Hair et al., 2019). Next, assessing the structural model involves examining the R2, which indicates the explanatory capacity of a model, and f2, which indicates the effect size of exogenous variables on endogenous ones (Cohen, 1988), as detailed in Table 4. The R2 value (Table 4) stands at 0.168, revealing that the exogenous variables cause 16% of the dependent variable’s variance. After that, the f2 values were used to find out how big the effect of each exogenous variable was. The f2 values for attitude and PI had a big effect on both PI and purchase behaviour, with values of 0.201. However, other constructs have little to no effect on PI. The hypotheses are assessed by conducting bootstrapping functions with 10,000 subsamples at a 5% significance level. Table 4 shows the results of the structural model. It shows that all of the direct relationships are important, except for the ones from environmental consciousness (EC) to PI, purchase behaviour control (PBC) to PI, and subjective norms (SI) to PI. Consequently, hypotheses H1, H3, H4, H5, H7 and H9 are accepted, but H2, H6 and H8 are not. After that, we used mediation analysis to see if there was a mediation effect. For these to be significant, two conditions had to be met: the total effect of the relationship between the exogenous and endogenous variables had to be significant. The subsequent step is to figure out how important the indirect effect between independent and dependent constructs is through the mediating variable. When these two criteria are met, the mediating variable has a full mediating effect between the independent variable and the dependent variable. If the direct effect of an outside variable on an inside variable is strong when the mediator is there, the mediator is said to have a partial mediating effect (Hayes, 2009; Khan et al., 2022). Table 4 shows how PI affects the relationship between exogenous variables (PBC, AT, SN, EK, EC, GU, WP and HV) and endogenous variables (PB). The insignificant effects are PBC, SN and EC. Because of this, the mediation relationships suggested in H9b, H9d, H9f, H9g and H9h are confirmed, but the other mediation hypotheses do not have enough evidence to support them. In addition, Q2 values are used to check the model’s ability to make predictions on data. Q2 shows the predictive exactness of the model, and the values must be above 0 for any endogenous construct to establish the out-of-sample predictive exactness of the model (Hair et al., 2019), so the values of 0.2 and 0.5 (as shown in Table 4), that is, 20% and 50%, confirm the out of the sample predictive power of the model. Moreover, the overall model has a good model fit with an SRMR value less than 0.10.

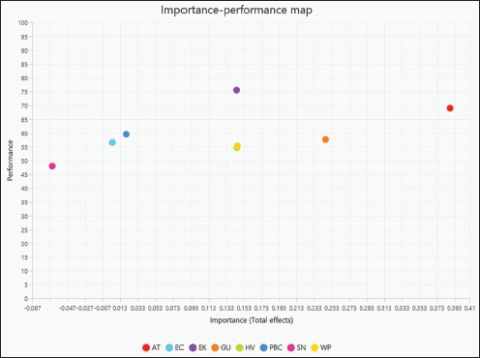

Importance–Performance Analysis (IPMA).

To strengthen and enhance the interpretation of path coefficients, Smart PLS has introduced a novel feature known as IPMA (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). IPMA shows the relative significance of all constructs in the model, gauged by their aggregate effects, juxtaposed with overall performance as indicated by their average variable scores (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). The primary purpose of IPMA is to show the constructs that have high importance yet exhibit low performance. In the IPMA Map (Figure 3), constructs positioned towards the right signify heightened importance. Policymakers and stakeholders of an entity should prioritise those constructs marked by high importance and low performance. While EK demonstrates the highest performance, its importance is relatively low. Therefore, practitioners are required to pay maximum attention to that construct. Practitioners should pay relatively less attention to constructs on the higher side than those on the right lower side (Ringle & Sarstedt, 2016). The construct of subjective norms should be accorded the least attention as it lies lowest in both importance and performance.

Table 4. Structural Model Results.

Figure 3. Importance–Performance Analysis Map.

Discussion

Our findings reveal that variables such as attitude, guilt, WP and HV occupy a pivotal place in creating sustainable clothing PIs among consumers. The study reported that perceived behavioural control, subjective norms, and EC have no significant bearing on purchasing intention for sustainable clothing, which implies that consumers do not perceive subjective norms, EC and perceived behavioural control to be substantial for intention to purchase sustainable clothing. The findings also reveal that HV for sustainable clothing significantly and positively affected sustainable purchasing intention. Moreover, variables like purchasing intention and purchase behaviour have a positive and significant relationship, signalling that modern youth positively translate their purchasing intention into purchase behaviour, and no intention–behaviour gap prevails. The study has attempted to bridge the significant gap in purchasing intention and PB for sustainable clothing by investigating the mediating effect of planned and extended planned behaviour variables. To the best of our understanding, this study is the first to incorporate the additional variables into the extended TPB and examine their total effect on PI in an integrated framework.

Conclusion

Our study adds fresh perspectives to the existing literature on sustainable clothing by expanding the TPB. It highlights the importance of understanding how younger consumers engage with sustainable fashion, a group that often drives trends and shapes market shifts. By applying a well-established theoretical framework known for explaining pro-environmental behaviours, such as the adoption of sustainable clothing, the research demonstrates that extending the traditional TPB model with additional variables can provide a richer and more nuanced understanding of consumer behaviour. Another important part is using mediation analysis, which makes it easier to present the results. Prior studies have reported that concentrating solely on direct relationships may neglect significant mediating effects, potentially resulting in incomplete conclusions (Nitzl et al., 2016). In this research, PI serves as a mediator connecting different elements of the TPB with actual sustainable clothing PB. Additionally, our research employed advanced techniques, including IPMA, a method infrequently utilised in PLS-SEM studies (Zahari & Esa, 2018). The IPMA assists professionals and marketers in determining the most significant and effective factors for practical implementation. The results show that marketers and policymakers need to focus on the variables that have the biggest effect on outcomes. Marketers should especially think about making campaigns that raise awareness on environmental issues that make youth realise the importance of conserving the environment. The analysis shows that EK should be given more importance because it is very important, but is not being used as much as it should be. Finally, marketers of sustainable clothing need to remember that modern youth not only prefer eco-friendly products; they also care about fashion and style.

Limitations and Future Research Agendas

It is important to acknowledge the limitations of any study, even though this study offers some insightful knowledge on youth intention to purchase sustainable clothing. These limitations offer avenues for potential study to build upon and improve the results. First, our study is confined to exploring the factors that affect PI and behaviour by youth towards sustainable clothing; the study overlooks other intervening variables that may affect this dynamic. Therefore, further studies should broaden the scope by analysing the effect of other intervening factors that may affect this relationship. Next, the current study has taken youth as respondents, and future studies can do a comparative analysis of various sections of society to bring out more insightful results. Moreover, this study has concentrated on the clothing industry in India; similar studies could be done in other sectors and economies, like sustainable energy in developed countries, which may feature diverse consumer profiles, thereby improving the generalisability of the findings. Future studies can expand upon the existing constructs by incorporating additional variables into the TPB. Lastly, the present study’s cross-sectional design provides a moment in time, making it hard to assess how the relationship among various determinants of PI and actual purchase behaviour changes over the period of time. Therefore, to address this problem, a longitudinal approach may be undertaken in the future. The above-mentioned limitations of the current study point to constructive directions for future studies. In spite of its limitations, the study contributes significantly to the body of research on how people buy clothes in a way that is good for the environment.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Stenzin Dawa  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7749-8896

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7749-8896

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.

Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1969). The prediction of behavioral intentions in a choice situation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 5(4), 400–416.

Aldilax, D., Hermawan, P., & Mayangsari, L. (2020). The antecedents of slow fashion product purchase decision among youth in Bandung, Jakarta, and Surabaya. KnE Social Sciences, 849–864.

Apaolaza, V., Policarpo, M. C., Hartmann, P., Paredes, M. R., & D’Souza, C. (2023). Sustainable clothing: Why conspicuous consumption and greenwashing matter. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(6), 3766–3782.

Babin, B. J., Darden, W. R., & Griffin, M. (1994). Work and/or fun: Measuring hedonic and utilitarian shopping value. Journal of Consumer Research, 20(4), 644–656.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1981). Attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A test of some key hypotheses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(4), 607.

Bamberg, S., & Möser, G. (2007). Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(1), 14–25.

Belk, R. (1975). Consumer behavior. The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of consumption and consumer studies. Journal of Consumer Research, 2(12), 157–164.

Birtwistle, G., & Moore, C. M. (2007). Fashion clothing: Where does it all end up? International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management, 35(3), 210–216.

Bly, S., Gwozdz, W., & Reisch, L. A. (2015). Exit from the high street: An exploratory study of sustainable fashion consumption pioneers. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(2), 125–135.

Busalim, A., Fox, G., & Lynn, T. (2022). Consumer behavior in sustainable fashion: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 46(5), 1804–1828.

Cheah, I., & Phau, I. (2011). Attitudes towards environmentally friendly products: The influence of ecoliteracy, interpersonal influence and value orientation. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 29(5), 452–472.

Cocquyt, A., Crucke, S., & Slabbinck, H. (2020). Organizational characteristics explaining participation in sustainable business models in the sharing economy: Evidence from the fashion industry using conjoint analysis. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(6), 2603–2613. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2523

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434.

Colucci, M., & Vecchi, A. (2021). Close the loop: Evidence on the implementation of the circular economy from the Italian fashion industry. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 856–873.

Connell, K. Y. H., & Kozar, J. M. (2014). Environmentally sustainable clothing consumption: Knowledge, attitudes, and behavior. In S. Muthu (Ed.), Roadmap to sustainable textiles and clothing (pp. 41–61). Springer.

Diddi, S., Yan, R. N., Bloodhart, B., Bajtelsmit, V., & McShane, K. (2019). Exploring young adult consumers’ sustainable clothing consumption intention–behavior gap: A behavioral reasoning theory perspective. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 18, 200–209.

Dijkstra, T. K., & Henseler, J. (2015). Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Quarterly, 39(2), 297–316.

Elf, P., Werner, A., & Black, S. (2022). Advancing the circular economy through dynamic capabilities and extended customer engagement: Insights from small sustainable fashion enterprises in the UK. Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(6), 2682–2699.

ElHaffar, G., Durif, F., & Dubé, L. (2020). Towards closing the attitude–intention–behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 275, 122556 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122556

Elliott, M. A., Armitage, C. J., & Baughan, C. J. (2003). Drivers’ compliance with speed limits: An application of the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 964.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

Florka, R. (2002). Consciousness and the mind of god. Faith and Philosophy, 19(1), 127–131.

Gangakhedkar, R., Khan, M., & Karthik, M. (2023). Understanding carpooling intentions of Generation Z of India: A structural equation modeling approach. Transportation Planning and Technology, 47(5), 728–748.

Goldsmith, K., Cho, E. K., & Dhar, R. (2012). When guilt begets pleasure: The positive effect of a negative emotion. Journal of Marketing Research, 49(6), 872–881.

Grazzini, L., Acuti, D., & Aiello, G. (2021). Solving the puzzle of sustainable fashion consumption: The role of consumers’ implicit attitudes and perceived warmth. Journal of Cleaner Production, 287, 125579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125579

Hair, J., & Alamer, A. (2022). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in second language and education research: Guidelines using an applied example. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 100027.

Hair, J. F., Harrison, D., & Risher, J. J. (2018). Marketing research in the 21st century: Opportunities and challenges. Brazilian Journal of Marketing-BJMkt, Revista Brasileira de Marketing–ReMark, Special Issue, 17. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3260856

Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152.

Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management and Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458.

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24.

Hair, J. F. Jr, Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & G. Kuppelwieser, V. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review, 26(2), 106–121.

Han, J., Seo, Y., & Ko, E. (2017). Staging luxury experiences for understanding sustainable fashion consumption: A balance theory application. Journal of Business Research, 74, 162–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.029

Hasnah Hassan, S. (2018). The role of Islamic values on green purchase intention. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 5(3), 379–395.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135.

Izard, C. E. (1997). 3. Emotions and facial expressions: A perspective from differential. The Psychology of Facial Expression, 57–77.

Jacobs, K., Petersen, L., Hörisch, J., & Battenfeld, D. (2018). Green thinking but thoughtless buying? An empirical extension of the value-attitude-behaviour hierarchy in sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1155–1169.

Jung, H. J., Choi, Y. J., & Oh, K. W. (2020). Influencing factors of Chinese consumers’ purchase intention to sustainable apparel products: Exploring consumer ‘attitude–behavioral intention’ gap. Sustainability, 12(5), 1770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12051770

Kang, J., Liu, C., & Kim, S. H. (2013). Environmentally sustainable textile and apparel consumption: The role of consumer knowledge, perceived consumer effectiveness and perceived personal relevance. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 37(4), 442–452.

Khan, M. M., Mubarik, M. S., Islam, T., Rehman, A., Ahmed, S. S., Khan, E., & Sohail, F. (2022). How servant leadership triggers innovative work behavior: Exploring the sequential mediating role of psychological empowerment and job crafting. European Journal of Innovation Management, 25(4), 1037–1055.

Kim, Y., & Oh, K. W. (2020). Which consumer associations can build a sustainable fashion brand image? Evidence from fast fashion brands. Sustainability, 12(5), 1703.

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10.

Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 13(7). https://aisel.aisnet.org/jais/vol13/iss7/2

Krause, D. (1993). Environmental consciousness: An empirical study. Environment and Behavior, 25(1), 126–142.

Kumar, A., Prakash, G., & Kumar, G. (2021). Does environmentally responsible purchase intention matter for consumers? A predictive sustainable model developed through an empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 58, 102270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102270

Kumar, B., Manrai, A. K., & Manrai, L. A. (2017). Purchasing behaviour for environmentally sustainable products: A conceptual framework and empirical study. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 1–9.

Kuswati, R., Purwanto, B. M., Sutikno, B., & Aritejo, B. A. (2021). Pro-environmental self-identity: Scale purification in the context of sustainable consumption behavior. Eurasian Business and Economics, 7, 173–185.

Lindenmeier, J., Lwin, M., Andersch, H., Phau, I., & Seemann, A. K. (2017). Anticipated consumer guilt: An investigation into its antecedents and consequences for fair-trade consumption. Journal of Macromarketing, 37(4), 444–459.

Liu, P., Teng, M., & Han, C. (2020). How does environmental knowledge translate into pro-environmental behaviors? The mediating role of environmental attitudes and behavioral intentions. Science of the Total Environment, 728, 138126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138126

Lundblad, L., & Davies, I. A. (2016). The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 15(2), 149–162.

Manaktola, K., & Jauhari, V. (2007). Exploring consumer attitude and behaviour towards green practices in the lodging industry in India. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 19(5), 364–377.

Mcneill, L., & Moore, R. (2015). Sustainable fashion consumption and the fast fashion conundrum: Fashionable consumers and attitudes to sustainability in clothing choice. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 39(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12169

Miao, L. (2011). Guilty pleasure or pleasurable guilt? Affective experience of impulse buying in hedonic-driven consumption. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 35(1), 79–101.

Mishal, A., Dubey, R., Gupta, O. K., & Luo, Z. (2017). Dynamics of environmental consciousness and green purchase behaviour: An empirical study. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 9(5), 682–706.

Mishra, A., & Mishra, H. (2011). The influence of price discount versus bonus pack on the preference for virtue and vice foods. Journal of Marketing Research, 48(1), 196–206.

Morren, M., & Grinstein, A. (2016). Explaining environmental behavior across borders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 47, 91–106.

Nassivera, F., Troiano, S., Marangon, F., Sillani, S., & Nencheva, I. M. (2017). Willingness to pay for organic cotton: Consumer responsiveness to a corporate social responsibility initiative. British Food Journal, 119(8), 1815–1825.

Niinimäki, K. (2010). Eco-clothing, consumer identity and ideology. Sustainable Development, 18(3), 150–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.455

Nitzl, C., Roldan, J. L., & Cepeda, G. (2016). Mediation analysis in partial least squares path modeling: Helping researchers discuss more sophisticated models. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1849–1864.

Park, H. J., & Lin, L. M. (2020). Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: Comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. Journal of Business Research, 117, 623–628.

Preuit, R., & Yan, R. N. (2016). Fashion and sustainability: Increasing knowledge about slow fashion through an educational module. International Textile and Apparel Association annual conference proceedings (Vol. 73(1)). Iowa State University Digital Press.

Punyatoya, P. (2015). Effect of perceived brand environment-friendliness on Indian consumer attitude and purchase intention: An integrated model. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 33(3), 258–275.

Ramanathan, S., & Williams, P. (2007). Immediate and delayed emotional consequences of indulgence: The moderating influence of personality type on mixed emotions. Journal of Consumer Research, 34(2), 212–223.

Rausch, T. M., & Kopplin, C. S. (2021). Bridge the gap: Consumers’ purchase intention and behavior regarding sustainable clothing. Journal of Cleaner Production, 278, 123882. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123882

Remy, N., Speelman, E., & Swartz, S. (2016). Style that’s sustainable: A new fast-fashion formula. McKinsey Global Institute. http://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability-and-resource-productivity/ourinsights/style-thats-sustainable-a-new-fast-fashion-formula

Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). Gain more insight from your PLS-SEM results: The importance–performance map analysis. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(9), 1865–1886.

Sadiq, M., Bharti, K., Adil, M., & Singh, R. (2021). Why do consumers buy green apparel? The role of dispositional traits, environmental orientation, environmental knowledge, and monetary incentive. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 62, 102643.

Saha, K., Dey, P. K., & Papagiannaki, E. (2022). Implementing circular economy in the textile and clothing industry. In P. K. Dey, S. Chowdhury, & C. Malesios (Eds), Supply chain sustainability in small and medium sized enterprises (pp. 239–276). Routledge.

Schlegelmilch, B. B., Bohlen, G. M., & Diamantopoulos, A. (1996). The link between green purchasing decisions and measures of environmental consciousness. European Journal of Marketing, 30(5), 35–55.

Sheppard, B. H., Hartwick, J., & Warshaw, P. R. (1988). The theory of reasoned action: A meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(3), 325–343.

Shukla, S. (2019). A study on millennial purchase intention of green products in India: Applying extended theory of planned behavior model. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 20(4), 322–350.

Trumbo, C. W., & O’Keefe, G. J. (2005). Intention to conserve water: Environmental values, reasoned action, and information effects across time. Society and Natural Resources, 18(6), 573–585.

Wiederhold, M., & Martinez, L. F. (2018). Ethical consumer behaviour in Germany: The attitude–behaviour gap in the green apparel industry. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42(4), 419–429.

Yadav, R., & Pathak, G. S. (2016). Young consumers’ intention towards buying green products in a developing nation: Extending the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 135, 732–739.

Zahari, A. R., & Esa, E. (2018). Drivers and inhibitors adopting renewable energy: An empirical study in Malaysia. International Journal of Energy Sector Management, 12(4), 581–600.