The Knowledge Blackout: Workplace Incivility, Contract Breaches, and the Light of Ethical Leadership

1Department of Management, ITM University, Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India

2Department of Management, Chandigarh School of Business, Chandigarh Group of Colleges Jhanjeri, Mohali, Punjab, India

Creative Commons Non Commercial CC BY-NC: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 License (http://www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits non-Commercial use, reproduction and distribution of the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed.

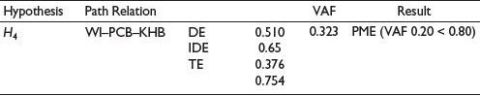

This study investigates the connection between workplace incivility (WI) and knowledge-hiding behavior (KHB) using knowledge from social learning theory. Drawing on a survey of 388 employees across various Indian organizations, analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), the study confirms that WI significantly increases KHB (β = 0.510, p < .01). It also reveals that psychological contract breach (PCB) mediates this relationship (VAF = 0.323), while ethical leadership (EL) plays a buffering role, weakening the adverse impact of WI on KHB. Results demonstrate that WI causes a rise in KHB, since employees facing incivility tend to withhold information exchanges because of work-related stress. PCB also supports the finding because expectations not met by employers or employees can lead to employees hiding important information from them. It was found that EL plays a moderating role, as moral leaders reduce the harmful impact of WI by strengthening fairness, transparency and trust.

Social learning theory, toxic work culture, trust and transparency, organizational behavior, knowledge management

Introduction

With the economy now driven by knowledge, knowledge management (KM) has become very important in organizations, contributing to greater innovation, smarter decisions, and better competitiveness. KM means an organization’s plans and efforts to improve how knowledge is used all around the company (Baskerville & Dulipovici, 2006). KM helps place vital information, skills, and understanding in the hands of staff, so that they can team up, resolve issues, and constantly improve their work. If organizations use strong KM tools, they promote learning throughout the organization, lessen the need for repetition, and increase both efficiency and performance (Antunes & Pinheiro, 2020). As a result, organizations now recognize that knowledge is very valuable and that effectively managing it is essential for their success. Yet, despite KM concentrating on making knowledge easily available, organizations tend to face obstacles, and one of the biggest obstacles is knowledge-hiding behavior (KHB). When employees intend to hide or refuse to share valuable knowledge with others, it is called KHB by Bari et al. (2020). This behavior might include: not sharing all the facts, not wanting to talk about vital details, or acting like they have no idea (Van Slyke & Belanger, 2020). KHB stands out because it harms the foundations of KM by preventing information from being shared and hindering teamwork. Knowledge hoarding by employees can harm those who miss out on helpful information and can also harm the company. Reducing workers’ ability to share knowledge can slow down innovation (Chin et al., 2024), allow inefficiencies to develop (Bari et al., 2020), and decrease how quickly teams can find solutions to problems (Liu et al., 2020), making it more challenging for the organization to respond effectively (Anand et al., 2020).

KHB often causes problems that relate to work culture and teams, and workplace incivility (WI) is a main driver of these issues (Haar et al., 2022). When people at work display WI, it usually means they act in a disrespectful way that can still drastically harm employee happiness and the company’s culture (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). When workers are treated rudely, they may deal with increased stress, reduce their job satisfaction, and lack confidence in their colleagues; thus, they might engage in ways that retaliate or defend themselves, including KHB (Wu et al., 2022). Because of this, staff may avoid helping one another and keep private facts when working with others who do not behave appropriately at work (Yao et al., 2020). As a result, acts of uncivil behavior at work harm organizational culture and negatively affect opportunities for colleagues to share what they know with each other (Xia et al., 2022). Psychological contract breach (PCB) is highly significant among the different causes of KHB. Employees create psychological contracts in their minds about what should be given and received from both sides, such as support for their career, job safety, and fairness. Owing to the breaking of trust, employees start to feel betrayed and unhappy. This usually leads to lower levels of involvement and performs counterproductive work, such as KHB (Ghani et al., 2020). A PCB causes employees to be less likely to offer their efforts and to keep information hidden from others (Liang, 2022). The breach damages their psychological attachment to the company, which discourages employees from helping each other with knowledge. Based on the structure created in this study, we propose that ethical leadership may moderate the relation between work importance and employees’ knowledge and health beliefs. Individuals in the workforce typically feel attracted to leaders with ethical values and a reliable reputation (Wu et al., 2022). The way a leader acts ethically shapes employees’ thoughts and behaviors, which then affect their relationships at work. According to studies, when leaders are ethical, employees share knowledge with their peers because they are committed to the organization and influenced by their leaders (Liu et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2022). Though research on KHB in organizations is increasing (Connelly et al., 2019), there is still a lot we do not understand about how it works in India.

Although global research on WI and KHB is robust, limited empirical studies contextualize these constructs within Indian organizational culture. In India, hierarchical workplace structures, collectivist values, and social identity pressures may uniquely influence how incivility is perceived and responded to by employees (Bijalwan et al., 2024; Jain et al., 2022). Existing studies, such as Agarwal et al. (2024) and Anand et al. (2023), have explored knowledge sharing and incivility, but few have examined the mediating role of PCB and the moderating effect of EL in Indian service- and knowledge-based sectors, where interpersonal dynamics are critical. Moreover, emerging Indian scholarship points to a rising prevalence of subtle incivilities in virtual and hybrid workplaces, yet the behavioral consequences like knowledge hiding remain underexplored (Ghani et al., 2020; Hassan et al., 2023). Therefore, this study addresses a specific gap by investigating how WI leads to KHB in Indian organizations, using PCB as a mediator and EL as a moderator, through quantitative analysis of data collected from 388 Indian professionals between July and December 2024. By focusing on the Indian organizational landscape, this study contributes to a culturally nuanced understanding of toxic work dynamics and KM challenges.

People in organizations have discussed knowledge hiding since it often leads to trust issues, poor careers and rivalries, which can make productivity, effectiveness, and growth more difficult depending on the intentions of the knowledge hider (Xiao & Cooke, 2019). Numerous studies have considered how things like organizational culture, a KM system, policies, goal focus, and politics affect knowledge hiding (Kaur & Kang, 2022; Koay et al., 2022). There is still a need to examine more closely what encourages knowledge hiding among employees (Irum et al., 2020). When negative affect is present, people tend to hide their knowledge, so studying which specific emotion leads to this behavior is necessary. The study aims to focus on the different interactions amongst WI, PCB, KHB, and EL. Understanding how these issues are linked helps employers bring about healthier relationships at work. By looking at how people who are mistreated at work hide information and how ethical leaders can prevent these issues, this study offers useful guidance on what supports or gets in the way of information sharing. The results help to guide decisions about improving knowledge sharing and encouraging transparency and teamwork. All in all, the study attempts to answer these research questions:

RQ1. How does WI influence KHB in organizations?

RQ2. What role does PCB play in the relationship between WI and KHB?

RQ3. Can EL moderate the impact of WI on KHB?

RQ4. How does EL foster a culture of knowledge sharing and reduce the incidence of knowledge hiding in the workplace?

Literature Review

WI and KHB

WI disrupts social interactions in organizations and is characterized as low-intensity deviant behavior with ambiguous intent to harm (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Empirical research links WI to various negative organizational outcomes, including burnout, emotional exhaustion, workplace withdrawal, and decreased performance and creativity (Butt & Yazdani, 2021). The negative consequences of incivility have been documented by previous researchers on employee attitudes and behaviors in the shape of knowledge hiding (Arshad & Ismail, 2018), low organizational commitment (Kabat-Farr et al., 2018), decreased job satisfaction (Jamal & Siddiqui, 2020), and decreased citizenship behavior (Yao et al., 2022). In response to incivility, individuals at the workplace may intentionally withhold knowledge by pretending that they lack access or awareness of the relevant knowledge/ information (Irum et al., 2020). KHB refers to the intentional withholding of valuable information, despite organizational efforts to promote knowledge sharing (Connelly et al., 2012). Employees often engage in rationalized hiding, playing dumb, or evasive knowledge hiding to avoid sharing requested information (Butt et al., 2023; Connelly et al., 2012). Research suggests that external pressures, dissatisfaction, and defensive motives contribute to KHB, negatively affecting organizational efficiency, employee trust, creativity, and turnover intentions (Cerne et al., 2017; Gagné et al., 2019; Jena & Swain, 2021). KHB is widespread across multiple domains, including the academic sector and healthcare, and results in reduced task performance, wasted resources, and impaired organizational innovation and commitment (Fong et al., 2018; Serenko & Bontis, 2016).

WI, which is an act of low-intensity deviant behavior characterized by unclear intent, has been steadily and reliably connected with poor psychological and behavioral consequences. As an illustration, Butt and Yazdani (2021) and Jamal and Siddiqui (2020) discovered that WI is positively linked to emotional exhaustion and low job satisfaction. Shahid and Kim (2019) extended the findings to show how responses in employees who experience WI might defensively respond to them through KHB as a retaliatory response or coping strategy. This is, however, not consistent with every study, as some exhibit differences in the directionality or strength of association. Indicatively, Fong et al. (2018) indicate that in cases where knowledge hiding is motivated by negative affect, it is only once in a while, as it is sometimes motivated by strategic self-protection or political actions, even in situations when no overt incivility occurs. This difference suggests a loophole in addressing the issue of emotional versus strategic motifs of KHB, a dimension that is inadequately addressed in the collectivistic societies such as India, where a balance between interpersonal harmony can moderate the act of vengeance.

Also, though some research (e.g., Cerne et al., 2017; Irum et al., 2020) speaks about the psychological effect of WI, the limited research does not compare differences in sectoral or cultural translation of the incivility to knowledge hiding. As an example, Anand et al. (2023) showed a greater WI–KHB relationship in Indian IT companies, and in the study of East-Asian companies, Jeong et al. (2022) found that knowledge hiding came about more due to job insecurity than incivility. Such a contrast shows a theoretical discrepancy in the case of dominant antecedents in all organizational contexts. Therefore, it is necessary not only to establish the WI–KHB association in an Indian context but also to understand whether PCB can be considered to act as a unifying cognitive process mediating the effects of employees irrespective of the motive: emotional, cultural, or strategic.

Therefore, when employees experience uncivil behavior at work, they often feel disrespected or marginalized, prompting defensive responses like withholding information. Prior research (e.g., Arshad & Ismail, 2018; Wu et al., 2022) confirms that WI reduces trust and collaboration, thus encouraging KHB.

H1: WI positively influences KHB.

Psychological Contract Breach as a Mediator

PCB refers to an employee’s perception that their employer has failed to fulfill promised obligations, often resulting from unmet expectations or unfair treatment (Robinson & Morrison, 2000; Suazo, 2009). PCB arises when the psychological needs that motivate employees, such as trust, fairness, and communication, are neglected by the organization (Afshan et al., 2021). Factors influencing PCB include employees’ perceptions and managerial behavior, where unmet promises can harm both the individual’s current job satisfaction and future career prospects (Jain et al., 2022).

When managers demonstrate favoritism or unfair treatment, it can lead to a perceived PCB, prompting employees to engage in counterproductive behaviors such as WI and KHB (Ahmed & Zhang, 2024; Bari et al., 2023). The breach of psychological contracts damages trust and weakens interpersonal relationships, fostering an atmosphere of distrust and dissatisfaction that hinders knowledge sharing (Bari et al., 2023). As a result, employees may purposefully withhold knowledge during meetings or demonstrate reduced engagement and productivity (Ghani et al., 2020). In this context, knowledge hiding becomes a defensive response to the PCB, where employees retaliate by concealing information, which further disrupts organizational performance (Ahmed & Zhang, 2024). PCB not only diminishes individual contributions but also leads to broader organizational challenges by fostering a culture of distrust and lowering overall productivity (Afshan et al., 2021).

Incivility violates employees’ implicit expectations of fairness, respect, and inclusion—core to the psychological contract. In the event of unmet expectations, employees perceive a breach, as evidenced in studies by Ahmed and Zhang (2024) and Afshan et al. (2021).

H2: WI positively influences PCB.

Employees who perceive a breach in psychological contracts often withdraw discretionary behaviors, such as knowledge sharing. This is supported by findings from Bari et al. (2023) and Ghani et al. (2020), which show PCB as a primary determinant of knowledge concealment.

H3: PCB positively influences KHB.

WI indirectly increases KHB by first triggering a perception of contract breach. This mediating role of PCB is consistent with Suazo (2009), who argues that PCB serves as a psychological link between workplace mistreatment and retaliatory behaviors like knowledge hiding.

H4: PCB mediates the relationship between WI and KHB.

Ethical Leadership

According to Brown and Treviño (2006), EL involves being fair, trustworthy, and respectful, helping create an atmosphere that encourages morally right behavior. The study shows that EL means three things: acting ethically, treating individuals equally, and keeping an eye on morality (Mayer et al., 2012). As a “moral manager,” a person must set ethical principles, give praise for ethical actions, and discourage bad actions which directly influence WI and how the workplace operates. Those who lead ethically make it clear that undertaking manipulative actions will have negative results (Den Hartog, 2015). Employees are motivated to follow ethical standards by their leaders who then shape their satisfaction, work performance, and willingness to share knowledge (Bedi et al., 2016). Creating employee training in the learning organization means giving workers clear boundaries, which reduces the instances of unethical actions (Hsieh et al., 2020). By rewarding transparency and punishing unethical actions, ethical leaders foster an environment where concealing or falsifying information is discouraged. Empirical studies show that EL significantly undermines employees’ engagement in knowledge hiding (Anser et al., 2020). Ethical leaders are seen as role models who guide employees toward ethical conduct and away from behaviors like KHB. Therefore, EL is expected to moderate the relationship between WI and KHB, reducing the probability of employees engaging in knowledge hiding despite incivility in the workplace. Ethical leaders act as moral role models and reduce the impact of toxic behaviors by promoting trust and transparency. Studies by Brown and Treviño (2006) and Anser et al. (2020) support EL’s buffering role in mitigating the negative consequences of WI.

H5: EL moderates the relationship between WI and KHB, such that the relationship is weaker under high EL.

Theoretical Framework

Social Learning Theory

We have adopted the social learning theory (Bandura & Adams, 1977) in this study to explicate whether and how WI, PCB, and EL relate to knowledge hiding in the workplace. Social learning theory suggests that individuals are likely to emulate the behavior of role models within professional settings. Accordingly, ethical leaders’ proactive communication about what is (un-)ethical behavior and their open and transparent knowledge sharing give employees a model of what is (in-)appropriate behavior at work (Bouckenooghe et al., 2015; Gok et al., 2017). Thus, social learning theory may be a valuable lens for investigating why employees are less likely to hide or conceal their knowledge while under EL (Men et al., 2020). Drawing insights from social learning theory (Bandura & Adams, 1977), we explored the influence of WI and EL on employees’ KHBs. Furthermore, the research investigates the underlying psychological processes by which WI impacts employees’ tendencies to hide knowledge.

Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory

In accordance with Hobfoll’s COR theory from 1989, people make a concerted effort to develop, protect, and preserve their assets. Assets are elements that hold significance because they make it easier to obtain or preserve other valuable resources (Hobfoll, 2001), and they are a way to acquire more things, energies, conditions, or individual traits (Hobfoll, 1989). Resources include things, situations, and states that have value to people. COR theory explains the motivation of employees to place a strong emphasis on preserving one’s resources and knowledge. As per the COR theory, a lack or loss of valuable resources could make life difficult for people when they encounter new stressors (Hobfoll, 1989). As a result, these people might exhibit more unfavorable work outcomes to make up for the resource loss, and they may display defensive behavior as well as show reluctance to divulge their knowledge when they perceive an existential threat to their reserves, becoming knowledge hiders. Therefore, the COR theory can be used to clarify how rudeness at work affects knowledge hiding.

The inclusion of both social learning theory and COR theory offers a complementary understanding of KHB. While social learning theory explains how employees observe and replicate EL to model prosocial knowledge-sharing behaviors, COR theory addresses the defensive reactions to resource loss caused by incivility. Using both frameworks enables the study to capture both the social-cognitive process (through leadership influence) and the resource-protection mechanism (through PCB) that jointly drive knowledge hiding. Thus, their integration strengthens the explanatory power of the model across both motivational and behavioral dimensions.

Research Methodology

Data Collection

The study used a structured questionnaire comprising established and validated scales from prior peer-reviewed studies. WI was measured using the 12-item scale adapted from Cortina et al. (2001). PCB was assessed using the 8-item scale by Robinson and Morrison (2000). KHB was measured with the 12-item scale from Connelly et al. (2012), and EL was evaluated using the 10-item scale by Brown and Treviño (2006). Responses were measured using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

Prior to data collection, the study adhered to ethical research guidelines. While formal approval was not sought from a university ethics board due to the nonsensitive and anonymous nature of the survey, all participants were provided with an informed consent form explaining the purpose of the study, ensuring confidentiality and voluntary participation. No personal identifiers were collected. Snowball sampling was chosen due to the challenge of accessing a large, diverse sample of full-time professionals across different sectors in India. It enabled researchers to reach employed individuals across regions through professional networks, especially during ongoing remote and hybrid work arrangements. However, this nonprobability sampling method may limit generalizability, as the sample may overrepresent certain sectors or networks. This limitation is acknowledged, and future research is encouraged to use stratified or random sampling for broader representativeness.

Participants responded to survey questions using a 5-point Likert scale, from disagreeing to agreeing and the survey was completed from July to September 2023. We followed Faul et al. (2009) and used G*Power software to set the number of respondents necessary for our study. To make sure the power is at 0.80 and the alpha level is 0.05, it was decided that 159 is the minimum sample size. The high number of participants, 388 versus only 159 required, made this study able to follow the criteria for sample size.

Common Method Bias

Common method bias (CMB) is a major issue that must be taken into account when carrying out a survey, as it often happens. This predominantly takes place when data are collected from a single resource (Avolio et al., 1991). A full collinearity approach, as outlined by Kock (2015), was applied to check if the CMB exists within the variance inflation factor (VIF). All the constructs used in this study had an inner VIF value below the threshold of 3.3. As a consequence, our study could not point to CMB as an issue. SRMR measures how accurately the model describes the data and it needs to be lower than 0.08 (according to Henseler et al., in 2015). With the current model, the SRMR is 0.072, which is under 0.08, the critical value. The research model’s predicted correlation matrix matched the empirical one and had an SRMR smaller than the reasonable critical value.

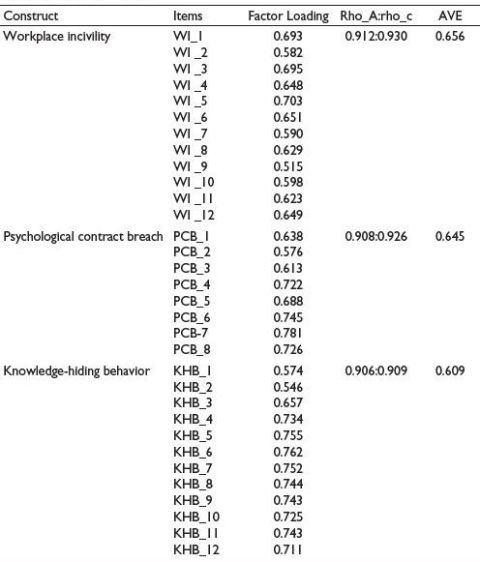

Table 1. Construct Validity.

Measurement Model

Internal consistency reliabilities, composite reliability, and Henseler’s rhoA for reflective constructs were used to evaluate the measurement model within the tolerance range of 0.70–0.95 (Hair et al., 2019; Sarstedt et al., 2021) (see Table 1). Average variance extracted was utilized to determine convergent validity; some of the reflective constructs did not exceed the threshold of 0.50. In the case of such constructs, the composite reliability exceeded the limit of 0.60, thus reaching the necessary value. All reflective constructs exceeded the critical value of 0.50 (Sarstedt et al., 2021).

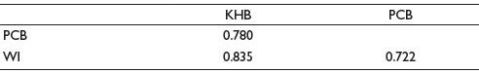

Table 2. Discriminant Validity.

Note: KHB: Knowledge-hiding behavior; PCB: Psychological contract breach; WI: Workplace incivility.

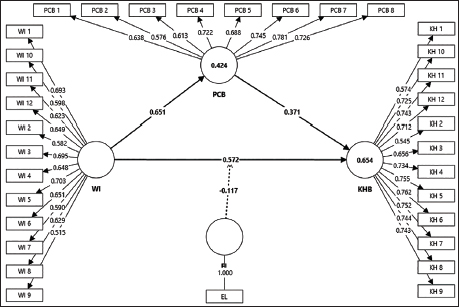

Figure 1. Structural Model.

Heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations was employed to test the discriminant validity (Henseler et al., 2015). HTMT was 0.65, which was below the tolerance limit of 0.85 (Gold et al., 2001) (see Table 2). Thus, it is concluded that the discriminant validity of the current measurement model is not impacted.

Structural Model

The evaluation of the structural model (see Figure 1) was carried out in agreement with the recommendations made by Sarstedt et al. (2021). The VIF inner values, which were discovered to be less than the critical value of 3.33 (Hair et al., 2019), were used to assess the collinearity issues. The structural model was evaluated based on the following metrics: path coefficients (β), R2, F2, and confidence interval for examining the causal relationships between the investigated latent variables (Sarstedt et al., 2021). Variation in the model is shown by the R2 value. With the estimated R2 for the latent variables, the explanatory power of the model has improved, as seen in KHB’s R2 value of 0.651 and PCB’s R2 value of 0.424.

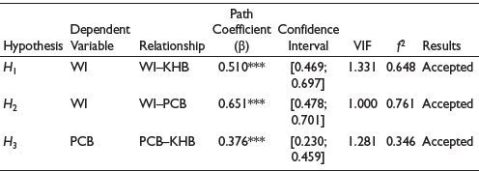

WI explains 42% of the differences seen in PCB and 65.1% in the variance of KHB. Hypothesis testing using the bootstrapping method was followed by the previous step. Moreover, 10,000 subsamples of bootstrapping were used to evaluate the structural model results (Sarstedt et al., 2021). Table 3 depicts the results of the structural model. H1, H2, H3, and H4 are supported as a result of the findings that WI exhibits a strong and favorable effect on KHB (β = −0.651, p = .01), PCB (β = −0424, p = .01), and PCB has a significant and positive effect on KHB (β = −0.376, p = .01) (see Table 3).

Table 3. Structural Model Assessment.

Table 4. Mediation Analysis.

Notes: WI: Workplace incivility; EL: Ethical leadership; KHB: Knowledge-hiding behavior; DE: Direct effect; IDE: Indirect effect; TE: Total effect; VAF: Variance accounted for; PME: Partial mediation.

F2 values of 0.02 to 0.15 indicate small effects, 0.15 to 0.35 indicate medium effects, and f2 values of >0.35 indicate large effects. All combinations of the variables in the study showed small, large, and medium effect sizes. Such values confirm that the research model is very useful for forecasting.

According to hypothesis 4, PCB appears to mediate the relationship between WI and KHB. The impact of PCBs on employee attitudes is shown in Table 4. The partial mediation of knowledge hiding by workplace rudeness is supported by a VAF of 0.323 (VAF 0.20 < 0.80).

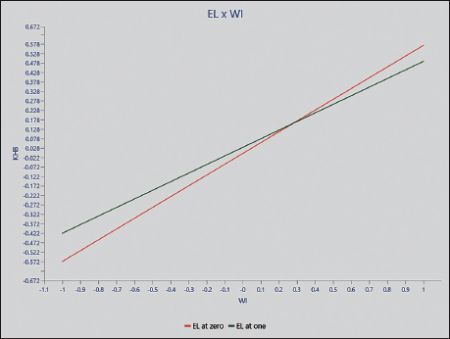

Moderation Analysis

The moderation analysis shown in Figure 2 investigates the role of emotional labor (EL) in influencing the strength of the relationship between WI and KHB, testing hypothesis 5. The interaction plot includes two simple slopes: one for low EL (red line) and one for high EL (green line). These lines illustrate how the effect of WI on KHB varies depending on the level of EL required from employees. At low levels of EL, the red slope indicates a weaker positive relationship between WI and KHB. These findings indicate that employees who are less involved in emotional regulation may experience incivility as less psychologically depleting; therefore, they are less inclined to engage in knowledge hiding as a defense. These individuals may emotionally detach or employ disengagement strategies to cope with incivility, thereby buffering its negative impact on knowledge-sharing behaviors (Chi et al., 2013).

Figure 2. Moderation Analysis.

Note: EL: Ethical leadership; WI: Workplace incivility.

In contrast, at high levels of EL, the green slope becomes significantly steeper, revealing a stronger positive relationship between WI and KHB. EL, particularly deep acting, is linked to sustained emotional regulation and increased cognitive load (Grandey, 2000), which may leave employees more susceptible to negative events like incivility. When emotional reserves are depleted, knowledge hiding can emerge as a coping mechanism, a way to conserve remaining psychological and interpersonal resources (Hobfoll, 1989; Liu & Roloff, 2015). The results align with the COR theory, which posits that individuals strive to obtain, retain, and protect resources. When EL is high, and employees are simultaneously exposed to incivility, they are likely to perceive themselves as resource-depleted, prompting defensive behaviors like knowledge hiding (Halbesleben et al., 2014). Moreover, EL may amplify emotional sensitivity, making even low-intensity incivility more impactful (Rupp et al., 2008). The positive interaction between EL and WI, therefore, suggests that EL exacerbates the negative consequences of incivility. Employees who are both emotionally taxed and mistreated are more prone to retreat from organizational citizenship behaviors, such as knowledge sharing, and instead may act in ways that protect themselves, even if counterproductive. This highlights the critical need for organizational interventions. When emotional display rules are rigid and incivility is unchecked, employees operate in environments that facilitate both psychological exhaustion and covert retaliation. To prevent the deterioration of knowledge-sharing culture, organizations must prioritize emotional support systems, encourage civility training, and implement emotional regulation flexibility in service roles.

Discussion

The rapid expansion of globalization has led to greater difficulties for companies to compete in today’s knowledge economy. Firms in this environment have to respond quickly to new market trends and make use of their team members, as their experienced staff gives them a strong advantage (Miceli et al., 2021). Still, using employees’ skills and knowledge properly depends on having effective KM (Lam et al., 2021). It includes merging staff members’ skills with the things a company has and the procedures it uses to support innovation. Being successful as an organization mainly depends on acquiring and sharing knowledge to strengthen innovation. Despite organizations working to encourage people to share knowledge, many actively withhold it (KHB). KHB concerns organizations greatly because it disrupts teamwork, reduces creativity, and damages how well an organization performs (Jeong et al., 2022). Grounded in social learning theory, this research explores the function of WI in influencing KHB. WI is defined as low-intensity deviant behavior characterized by ambiguity in its intent to harm (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). It disrupts workplace dynamics, erodes trust, and fosters negative attitudes, potentially leading employees to withhold knowledge as a form of self-protection or retaliation (Irum et al., 2020). This study also explores the mediating role of PCB and the moderating influence of EL in the WI–KHB relationship.

Results from the current study confirmed hypothesis 1, that WI raises KHB. This result is compatible with previous studies (Agarwal et al., 2024; Anand et al., 2023), which demonstrated that incivility causes employees to hide their knowledge from colleagues. Subjects of incivility might restrict their sharing of information to relieve the stress caused by dealing with people in stressful or unpleasant situations. With rising rude behavior, individuals are less inclined to share their experience with the group, which reduces both innovative and effective performance in the organization (Bijalwan et al., 2024). Moreover, the researchers looked at whether PCBs affected how WI was linked to KHB. Data revealed that Bari et al. (2023) and Ghani et al. (2020) were right about PCB being a crucial element that shapes KHB. Psychological contracts explain the personal commitments employees think should exist between them and their employer. When employees feel these rules are broken, for example, when what was promised to them is not delivered or if they receive unfair treatment, they go through a psychological contract break (Bari et al., 2023). A breach of this trust causes employees to feel upset and betrayed by their workplace. Thus, employees could try to withhold information in response. Research supports this point by showing that when anticipated outcomes fail to materialize, it often leads employees to hide important information (Ghani et al., 2020). This meant exploring whether EL had a function in blocking the effects of WI on KHB. Moral role models, ethical leaders foster a fair, trusting, and open environment among their team (Brown and Treviño, 2006). Higher EL was shown to significantly decrease the negative effects of WI on KHB (Anand et al., 2023). Ethical leaders outline what good behavior should look like, stop knowledge hiding, and ensure that openness and respect are valued throughout the team (Almeida et al., 2022). Even though employees’ personal beliefs could influence how they respond to leaders, extensive research has consistently demonstrated that ethical leaders have a strong influence on their employees (Almeida et al., 2022; Hassan et al., 2023).

The study’s outcomes are in agreement with the existing literature that links WI to increased knowledge hiding (e.g., Anand et al., 2023; Arshad & Ismail, 2018), affirming that WI undermines trust and promotes defensive knowledge behaviors. In contrast to earlier studies, this research offers a culturally grounded perspective from India, where hierarchical work structures and relational norms shape employee responses. For example, Agarwal et al. (2024) found that Indian employees often internalize incivility, which may exacerbate cognitive strain and trigger knowledge withholding even in the absence of overt conflict. Moreover, this study sets itself apart by empirically validating PCB as a partial mediator, a mechanism not extensively tested in prior Indian studies on knowledge hiding. While Ghani et al. (2020) and Bari et al. (2023) proposed the role of psychological mechanisms, our findings quantify this mediating path and establish its significance (VAF = 0.323). Additionally, the moderation analysis highlights that EL can significantly weaken the negative effects of WI on knowledge hiding, extending the theoretical application of social learning theory and COR theory to Indian knowledge workers. Most Indian and Asian studies tend to focus on either antecedents of incivility or implications of knowledge hiding in isolation. This study integrates both antecedent (WI), mediator (PCB), and moderator (EL) in a unified structural model, offering a holistic explanation of how toxic behavior translates into dysfunctional knowledge practices and how leadership can counteract this trajectory.

Implications

The research has a substantial contribution to the field of psychological management. This study shed light on WI and its adverse impacts on employees’ KHB. First, it adds to the theoretical foundation of the WI. This research is based on theories such as social exchange theory and COR theory. The impact of WI contributes to the theories of social exchange theory and COR theory. Once a psychological contract in an organization is ruptured, resources erode. These resources are disrupted, and employees begin to behave negatively. This situation leads to the hiding of necessary knowledge (Ghani et al., 2020). In this way, the performance of firms gets compromised. Current research findings also add to the KM theory by indicating that KH at any level of organization badly affects productivity (Anand et al., 2023). Hence, it adds to the body of existing research by suggesting the precursors of employees’ KHBs. Moreover, the results strengthen the social exchange theory by suggesting that incivility in workplace leads to PCB and KHB.

This research provides valuable insights for managerial practice. It offers insights to the managers and executives of the firms. The executives must pay heed to the psychological contracts of the employees (Bari et al., 2023). They should not disregard the psychological contracts. Managers and executives should take steps toward eradicating KH behaviors and they should foster a supportive and positive environment for the staff, which inspires them to participate in morally good practices in the workplace. Overall, this research is quite helpful for future researchers. Employees could be coached on how norms for respect develop (i.e., through fair and respectful treatment) and activities that disrupt these norms from forming (i.e., through unjust or unkind treatment from leaders) (Gosselin & Ireland, 2020). Failure to address incivility can lead to employees perceiving discrepancies between what leaders advocate and what is practiced, worsening workplace morale. It is also imperative that leaders deliberately cultivate and model the type of interpersonal behavior that conveys a clear message of respect. That is, managers should follow through on what they encourage while minimizing gaps between stated causes and perceived behaviors. Leaders who assert that they promote a respectful workplace but do not appropriately discipline employees who engage in harassing behaviors toward others may foster employees’ negative perceptions of norms for respectful treatment (Andersson & Pearson, 1999). Coaching leaders to develop the skills needed to be respectful of others represents a viable point of intervention (Olsen et al., 2020). Finally, when organizations identify and plan specific interventions to check incivility, they must consider the impacts of coworkers on employee perceptions of the normative environment, in addition to the role of charismatic and EL in fostering positive norms for respect (Walsh et al., 2017).

This study extends COR theory by empirically demonstrating how perceived WI leads to resource depletion through PCB, ultimately triggering defensive behaviors such as knowledge hiding. COR theory posits that individuals strive to conserve valued resources such as trust, emotional energy, and psychological safety and respond to threats with protective mechanisms. This research contributes a novel insight by positioning knowledge hiding as a behavioral manifestation of resource conservation within the realm of social contract violations. Moreover, by showing that the effect is conditioned by the presence of EL, the study adds depth to COR theory by integrating social–environmental buffers that can mitigate the loss spiral. This positions COR not only as a stress–response model but also as a framework that accounts for the interactive role of leadership in resource protection and restoration.

Limitations and Future Scope

In line with existing social research, this study has some limitations that may serve as an opportunity for scholars to conduct further research. First, the sample size of this study is limited, and hence the findings may not be generalizable; future research may increase the sample size to improve the reliability of the results. A longitudinal approach may be beneficial for future research to understand the impact of WI, as it has been posited that longer time frames may be suitable, as it can take time to recognize a pattern of incivility in the workplace (Cortina et al., 2017). Second, a structured questionnaire is employed in this research to collect data; future studies may consider other data collection methods, such as semi-structured, open-ended, and interview methods to as to get more detailed and in-depth information. Third, this study analyzed the impact of WI on KHB, through the mediating effect of PCB. Subsequent research could incorporate additional mediating variables such as cynicism and emotional exhaustion to broaden the understanding of the other antecedents which impacts employees’ KHB. Finally, this study predicts the moderating role of EL; future studies may further introduce other moderating variables like spiritual leadership, servant style leadership or workplace spirituality to validate the present study’s findings.

Conclusion

This study provides clear empirical evidence that WI significantly increases KHB among employees, wherein PCB functions as a key mediating mechanism. Additionally, it shows that EL acts as a modifier in this dynamic, helping to reduce the negative impact of incivility on knowledge-sharing practices. These findings are significant as they demonstrate how organizational climate and leadership style can either erode or protect critical intangible resources like trust and collaboration, especially in knowledge-driven industries. By validating this framework in an Indian context, the study contributes culturally grounded insights to both COR theory and social learning theory, showing how psychological resource loss and observational learning processes interact in shaping employee behavior. Future research should replicate this model using longitudinal data to capture the dynamic evolution of contract breach and knowledge hiding over time. Additionally, incorporating qualitative methods may reveal deeper narratives behind why employees conceal knowledge and how leaders actively intervene in such situations.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Afshan, G., Serrano-Archimi, C., & Lacroux, A. (2021). Raising voice: Effect of psychological contract breach on employee voice through organizational cynicism. Human Systems Management, 40(6), 857–869. https://doi.org/10.3233/hsm-201108

Agarwal, U. A., Singh, S. K., & Cooke, F. L. (2024). Does co-worker incivility increase perceived knowledge hiding? The mediating role of work engagement and turnover intentions and the moderating Role of cynicism. British Journal of Management, 35(3), 1281–1295. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12759

Ahmed, M. A. O., & Zhang, J. (2024). Investigating the effect of psychological contract breach on counterproductive work behavior: The mediating role of organizational cynicism. Human Systems Management, 43(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.3233/hsm-230010

Almeida, J. G., Hartog, D. N. D., De Hoogh, A. H., Franco, V. R., & Porto, J. B. (2022). Harmful leader behaviors: Toward an increased understanding of how different forms of unethical leader behavior can harm subordinates. Journal of Business Ethics, 180(1), 215–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-021-04864-7

Anand, A., Agarwal, U. A., & Offergelt, F. (2023). Why should I let them know? Effects of workplace incivility and cynicism on employee knowledge hiding behavior under the control of ethical leadership. International Journal of Manpower, 44(2), 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijm-04-2021-0248

Anand, A., Centobelli, P., & Cerchione, R. (2020). Why should I share knowledge with others? A review-based framework on events leading to knowledge hiding. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 33(2), 379–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-06-2019-0174

Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for tat? The spiraling effect of incivility in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1999.2202131

Anser, M. K., Ali, M., Usman, M., Rana, M. L. T., & Yousaf, Z. (2020). Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: An intervening and interactional analysis. The Service Industries Journal, 41(5–6), 307–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2020.1739657

Antunes, H. D. J. G., & Pinheiro, P. G. (2020). Linking knowledge management, organizational learning and memory. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 5(2), 140–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2019.04.002

Arshad, R., & Ismail, I. R. (2018). Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding behavior: Does personality matter? Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 5(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1108/joepp-06-2018-0041

Avolio, B. J., Yammarino, F. J., & Bass, B. M. (1991). Identifying common methods variance with data collected from a single source: An unresolved sticky issue. Journal of Management, 17(3), 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700303

Bandura, A., & Adams, N. E. (1977). Analysis of self-efficacy theory of behavioral change. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1(4), 287–310. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01663995

Bari, M. W., Ghaffar, M., & Ahmad, B. (2020). Knowledge-hiding behaviors and employees’ silence: Mediating role of psychological contract breach. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(9), 2171–2194. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-02-2020-0149

Bari, M. W., Khan, Q., & Waqas, A. (2023). Person related workplace bullying and knowledge hiding behaviors: Relational psychological contract breach as an underlying mechanism. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(5), 1299–1318. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-10-2021-0766

Baskerville, R., & Dulipovici, A. (2006). The theoretical foundations of knowledge management. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 4(2), 83–105. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500090

Bedi, A., Alpaslan, C. M., & Green, S. (2016). A meta-analytic review of ethical leadership outcomes and moderators. Journal of Business Ethics, 139, 517–536. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2625-1

Bijalwan, P., Gupta, A., Johri, A., & Asif, M. (2024). The mediating role of workplace incivility on the relationship between organizational culture and employee productivity: A systematic review. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2382894. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2024.2382894

Bouckenooghe, D., Zafar, A., & Raja, U. (2015). How ethical leadership shapes employees’ job performance: The mediating roles of goal congruence and psychological capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 129, 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2162-3\

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

Butt, A. S., Ahmad, A. B., & Shah, S. H. H. (2023). Role of personal relationships in mitigating knowledge hiding behaviour in firms: A dyadic perspective. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 53(4), 766–784. https://doi.org/10.1108/vjikms-01-2021-0009

Butt, S., & Yazdani, N. (2021). Influence of workplace incivility on counterproductive work behavior: Mediating role of emotional exhaustion, organizational cynicism and the moderating role of psychological capital. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences (PJCSS), 15(2), 378–404. https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/237082/1/1766511570.pdf

Černe, M., Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(2), 281–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12132

Chi, N.-W., Grandey, A. A., Diamond, J. A., & Krimmel, K. R. (2013). Want a tip? Service performance as a function of emotion regulation and extraversion. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1337–1346. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022887

Chin, T., Shi, Y., Arrigo, E., & Palladino, R. (2024). Paradoxical behavior toward innovation: Knowledge sharing, knowledge hiding, and career sustainability interactions. European Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2024.06.005

Connelly, C. E., Černe, M., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2019). Understanding knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 779–782. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2407

Connelly, C. E., Zweig, D., Webster, J., & Trougakos, J. P. (2012). Knowledge hiding in organizations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(1), 64–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.737

Cortina, L. M., Magley, V. J., Williams, J. H., & Langhout, R. D. (2001). Incivility in the workplace: Incidence and impact. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 6(1), 64.

Cortina, L. M., Kabat-Farr, D., Magley, V. J., & Nelson, K. (2017). Researching rudeness: The past, present, and future of the science of incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 299.

Den Hartog, D. N. (2015). Ethical leadership. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav, 2(1), 409–434. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032414-111237

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.41.4.1149

Fong, P. S., Men, C., Luo, J., & Jia, R. (2018). Knowledge hiding and team creativity: The contingent role of task interdependence. Management Decision, 56(2), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1108/md-11-2016-0778

Gagné, M., Tian, A. W., Soo, C., Zhang, B., Ho, K. S. B., & Hosszu, K. (2019). Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: The role of motivating work design. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(7), 783–799. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2364

Ghani, U., Teo, T., Li, Y., Usman, M., Islam, Z. U., Gul, H., Naeem, R. M., Bahadar, H., Yuan, J., & Zhai, X. (2020). Tit for tat: Abusive supervision and knowledge hiding-the role of psychological contract breach and psychological ownership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1240. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041240

Gok, K., Sumanth, J. J., Bommer, W. H., Demirtas, O., Arslan, A., Eberhard, J., Ozdemir, A. I., & Yigit, A. (2017). You may not reap what you sow: How employees’ moral awareness minimizes ethical leadership’s positive impact on workplace deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 146, 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3655-7

Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A., & Segars, A. H. (2001). Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. Journal of Management Information Systems, 18(1), 185–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2001.11045669

Gosselin, T. K., & Ireland, A. M. (2020, June). Addressing incivility and bullying in the practice environment. In Seminars in oncology nursing (Vol. 36, No. 3, p. 151023). WB Saunders. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2020.151023

Grandey, A. A. (2000). Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.1.95

Haar, J., O’Kane, C., & Cunningham, J. A. (2022). Firm-level antecedents and consequences of knowledge hiding climate. Journal of Business Research, 141, 410–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.034

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ebr-11-2018-0203

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hassan, S., Kaur, P., Muchiri, M., Ogbonnaya, C., & Dhir, A. (2023). Unethical leadership: Review, synthesis and directions for future research. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(2), 511–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05081-6

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43, 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hsieh, H. H., Hsu, H. H., Kao, K. Y., & Wang, C. C. (2020). Ethical leadership and employee unethical pro-organizational behavior: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and coworker ethical behavior. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 41(6), 799–812. https://doi.org/10.1108/lodj-10-2019-0464

Irum, A., Ghosh, K., & Pandey, A. (2020). Workplace incivility and knowledge hiding: A research agenda. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 27(3), 958–980. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-05-2019-0213

Jain, N., Le Sante, D., Viswesvaran, C., & Belwal, R. (2022). Incongruent influences: Joint effects on the job attitudes of employees with psychological contract breach in the MENA region. Review of International Business and Strategy, 32(3), 387–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/ribs-01-2021-0021

Jamal, R., & Siddiqui, D. A. (2020). The effects of workplace incivility on job satisfaction: Mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Human Resource Studies, 10(2), 56. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijhrs.v10i2.16389

Jena, L. K., & Swain, D. (2021). How knowledge-hiding behavior among manufacturing professionals influences functional interdependence and turnover intention. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 723938. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.723938

Jeong, J., Kim, B. J., & Kim, M. J. (2022). The impact of job insecurity on knowledge-hiding behavior: The mediating role of organizational identification and the buffering role of coaching leadership. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(23), 16017. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192316017

Kabat-Farr, D., Cortina, L. M., & Marchiondo, L. A. (2018). The emotional aftermath of incivility: Anger, guilt, and the role of organizational commitment. International Journal of Stress Management, 25(2), 109. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000045

Kaur, N., & Kang, L. S. (2022). Perception of organizational politics, knowledge hiding and organizational citizenship behavior: The moderating effect of political skill. Personnel Review, 52(3), 649–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-08-2020-0607

Koay, K. Y., Sandhu, M. S., Tjiptono, F., & Watabe, M. (2022). Understanding employees’ knowledge hiding behaviour: The moderating role of market culture. Behaviour and Information Technology, 41(4), 694–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2020.

1831073

Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijec.2015100101

Lam, L., Nguyen, P., Le, N., & Tran, K. (2021). The relation among organizational culture, knowledge management, and innovation capability: Its implication for open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010066

Liang, H. L. (2022). Façade creation as a mediator of the influence of psychological contract breach on employee behaviors. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 30(4), 614–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12379

Liu, F., Lu, Y., & Wang, P. (2020). Why knowledge sharing in scientific research teams is difficult to sustain: An interpretation from the interactive perspective of knowledge hiding behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 537833. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.537833

Liu, W., & Roloff, M. E. (2015). The interpersonal consequences of workplace incivility: The effects on targets and witnesses. Human Communication Research, 41(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12035

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55(1), 151–171. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2008.0276

Men, C., Fong, P. S., Huo, W., Zhong, J., Jia, R., & Luo, J. (2020). Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: A moderated mediation model of psychological safety and mastery climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(3), 461–472.

Miceli, A., Hagen, B., Riccardi, M. P., Sotti, F., & Settembre-Blundo, D. (2021). Thriving, not just surviving in changing times: How sustainability, agility and digitalization intertwine with organizational resilience. Sustainability, 13(4), 2052. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13042052

Olsen, J. M., Aschenbrenner, A., Merkel, R., Pehler, S. R., Sargent, L., & Sperstad, R. (2020). A mixed-methods systematic review of interventions to address incivility in nursing. Journal of Nursing Education, 59(6), 319–326. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20200520-04

Robinson, S. L., & Morrison, E. W. (2000). The development of psychological contract breach and violation: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(5), 525–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1379(200008)21:5

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Jones, K. S., & Liao, H. (2008). The utility of a multifoci approach to the study of organizational justice: A meta-analytic investigation into the consideration of targets of justice. Journal of Management, 34(6), 1124–1168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308324623

Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Hair, J. F. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of market research (pp. 587–632). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-57413-4_15

Serenko, A., & Bontis, N. (2016). Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 20(6), 1199–1224. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-05-2016-0203

Shahid, H., Chaudhry, S. A., Abbas, F., Ghulam Hassan, S., & Aslam, S. (2023). Do morality-based individual differences and relational climates matter? Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: a multilevel framework. SAGE Open, 13(4), 21582440231215569.

Suazo, M. M. (2009). The mediating role of psychological contract violation on the relations between psychological contract breach and work-related attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(2), 136–160. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910928856

Van Slyke, C., & Belanger, F. (2020). Explaining the interactions of humans and artifacts in insider security behaviors: The mangle of practice perspective. Computers and Security, 99, 102064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cose.2020.102064

Walsh, B. M., Lee, J., Jensen, J. M., McGonagle, A. K., & Samnani, A. K. (2018). Positive leader behaviors and workplace incivility: The mediating role of perceived norms for respect. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(4), 495–508.

Wu, Q., Saqib, S., Sun, J., Xiao, Y., & Ma, W. (2022). Incivility and knowledge hiding in academia: Mediating role of interpersonal distrust and rumination. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 769282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.769282

Xia, B., Wang, X., Li, Q., He, Y., & Wang, W. (2022). How workplace incivility leads to work alienation: A moderated mediation model. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 921161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.921161

Yao, J., Lim, S., Guo, C. Y., Ou, A., & Ng, J. W. X. (2022). Experienced incivility in the workplace: A meta-analytical review of its construct validity and nomological network. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(2), 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000870

Yao, Z., Zhang, X., Luo, J., & Huang, H. (2020). Offense is the best defense: The impact of workplace bullying on knowledge hiding. Journal of Knowledge Management, 24(3), 675–695. https://doi.org/10.1108/jkm-12-2019-0755